People in the News

Noah Creshevsky: A Personal Remembrance

Noah Creshevsky, a deeply resourceful and imaginative electronic composer, died at his home in New York City on December 3 at the age of 75. He had been suffering from cancer. He leaves behind his husband, David Sachs, and myriad colleagues who treasured his unfailing warmth, lively intelligence, and uncommon generosity of spirit.

Noah Creshevsky, a deeply resourceful and imaginative electronic composer, died at his home in New York City on December 3 at the age of 75. He had been suffering from cancer. He leaves behind his husband, David Sachs, and myriad colleagues who treasured his unfailing warmth, lively intelligence, and uncommon generosity of spirit.

Born in Rochester, NY, on January 31, 1945, he trained in Paris with legendary pedagogue Nadia Boulanger, studied with composer Luciano Berio at the Juilliard School, and became the director of the first Center for Computer Music at Brooklyn College, where he was a Professor Emeritus. His many recordings reflect an interest in what he termed “Hyperrealism,” an artistic approach using electronics to simulate acoustic instruments being played in a way that exceeded the bounds of human virtuosity. An early example was Circuit in 1971 for harpsichord on tape, and over the years the range and adventurousness of his output multiplied exponentially.

“Imagine all the world's instruments, musicians, and hemispheres lashed together into a giant mega-calliope, super-jukebox, or fantasmo-sampler,” wrote Arved Ashby in Gramophone. “As called to action by a hyper-caffeinated virtuoso, it might sound something like these works by Noah Creshevsky.” His most recent discs were produced on the Tzadik label, under the supervision of composer John Zorn, who became a Creshevsky champion. His compositions were invariably filled with color, invention, and, most strikingly, humor. No surprise—as a composer and as a person, he was utterly charming.

We first met when I was a student at Brooklyn College in the early 70s, and soon after we were colleagues at a summer performing arts program run by the college in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. We lost track of one another until, years later, we ran into each other at a contemporary music concert in Merkin Hall. “I know you!” he exclaimed with a broad smile, and the connection was instantly reestablished.

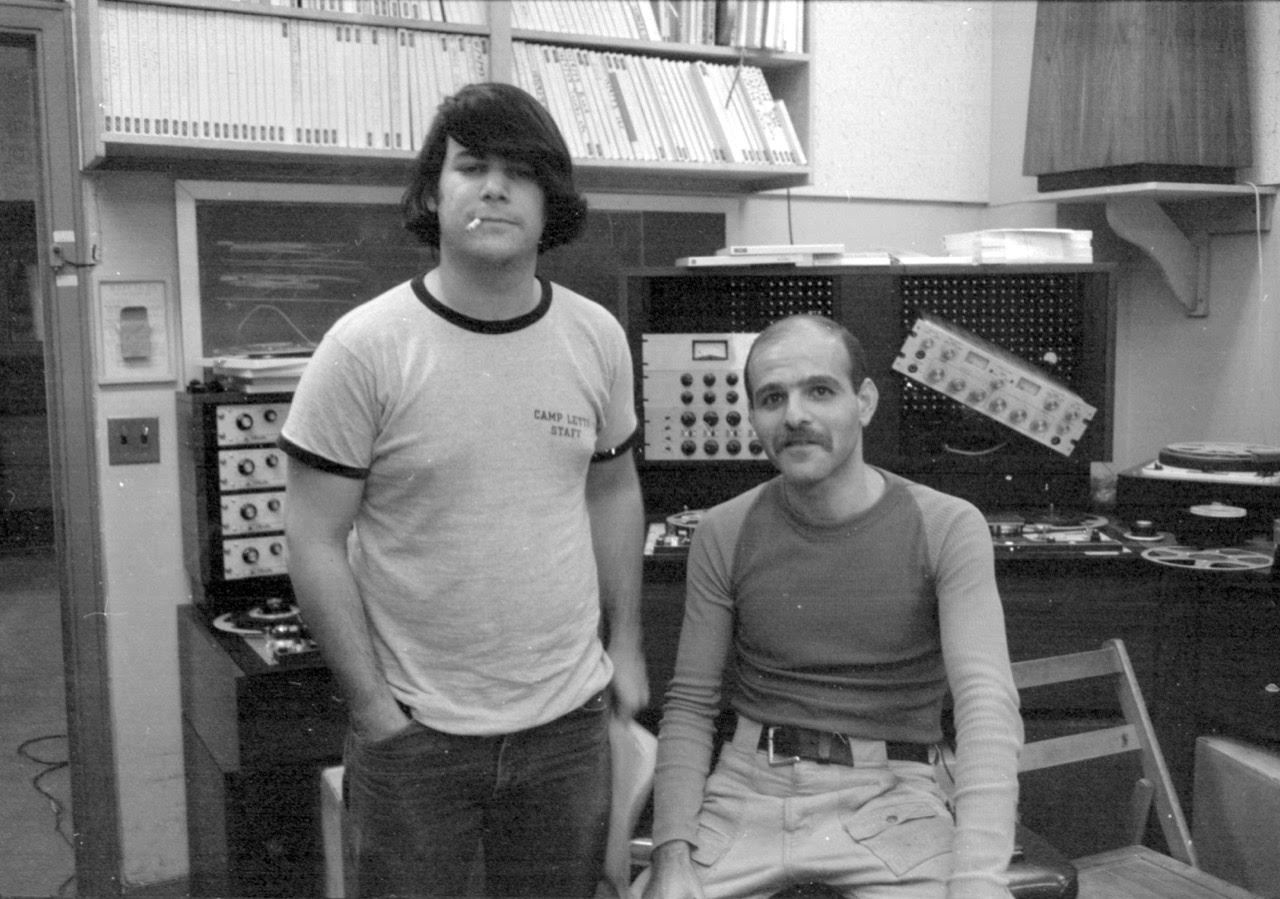

David Starobin (left) and Noah Creshevsky at Brooklyn College, 1975.

Photo by Glen Richards, courtesy Bridge Records, Inc.

We were both foodies, as witnessed by our expanding girths as we dined at favorite spots, like the Thai restaurants in his midtown neighborhood, or Katz’s Delicatessen on the lower East Side. When Noah became a vegetarian, he sympathetically offered to continue to meet me at Katz’s, but under those conditions, I declined: the pastrami-fueled thrill was gone. Still, there were other options, like the carb-heavy vegetarian restaurant in Chinatown, the rice pudding café on the lower West Side, and the lovely, quiet meals in Noah and David’s apartment, featuring appetizers from Zabar’s or Fairway—rare moments of solace and sanity in an increasingly insane world. At such times, I’d get small gems from him, like his recollections about life as a member of Virgil Thomson’s inner circle, or revelations about how Bach used parallel ninths.

Over the years, Noah and David became incessant cheerleaders on my behalf: regularly attending my lectures and piano performances, reading my articles and books with interest, and acting like loving uncles to my daughters. But the man was essentially private and shy, and he wouldn’t want me to engage in a lot of fuss, except perhaps about his music, of which he was justly proud.

The conceptions were spurred by a lifelong fascination with the idea of transcending human limitation. He once mentioned an uncle who did magic tricks from whom he had begged for explanations of how they were done. “When I finally learned the answers, I was disappointed,” he told me, “because the tricks became commonplace. Boulanger talked about this: How we lose the wonder of childhood and, as artists, have to recapture it somehow in a new, ‘informed’ second childhood. Music ought to be magic, and I’m always aiming for something that goes beyond the ordinary—I don’t even want to be able to put my finger on it.”

Transforming reality to magical

It spurred him to take materials that are recognizably of this world—real instrumental and vocal performances—and exaggerate them electronically, creating something that normal human beings are incapable of producing. He was aware, as a student, that Liszt was frequently criticized for empty virtuosity. “But I was always intrigued by that supreme degree of technical accomplishment. My music pushes virtuosity to new levels,” he said, “resulting in sounds that are lifelike and yet not real. I like that point which hovers between reality and the magical.”

He felt that electronic music holds a special place in the artform. “What is it that induces musicians to endlessly compose string quartet after string quartet, or an infinite number of pieces for solo piano?” he asked. “These prefabricated musical formats are generally chosen because composers imagine their music being played by live players in concert halls. In fact, most music is heard through speakers or headphones, at home. The home theater has nearly replaced the concert hall, especially in the area of contemporary non-pop music.

“Composing for recordings instead of for live concerts closes some doors, but opens others,” he insisted. “What of the composer who had dreamed of having a flutist imitate some bird sounds at the end of the last movement of a quartet that has been limited to four strings? Can we hire a flutist to play for only one minute of a 30-minute piece?”

Curated concerts of electronically produced and recorded works offer new possibilities in that regard, he maintained. “If this were a recording instead of a live concert, no one would care about the dramatic or economic comings and goings of the cello and flute. If this were a recording, and if the composer wanted birdcalls, he or she could make a recording of some real birds and dispense with the flutist altogether. If music—including music for standard ensembles—was conceived for recordings instead of live concerts, the music composed could be very different.” His works beautifully fulfilled that singular vision. It breaks my heart that he is gone.

Stuart Isacoff wrote the tribute to Musical America's 2021 Recording Artist of the Year, Igor Levit. Stuart is a pianist, writer, and the founder of Piano Today magazine, which he edited for nearly three decades. His latest book is When the World Stopped to Listen: Van Cliburn’s Cold War Triumph and Its Aftermath (Knopf).

FEATURED JOBS

FEATURED JOBS

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO