Reviews

A Celebration of Shostakovich

Nonpareil

LEIPZIG, Germany—When Dmitri Shostakovich died in 1975, the world lost one of the last composers whose work regularly touched the souls of listeners beyond the usual classical music crowd. Fifty years on, that is reason enough to celebrate his unique legacy with an 18-day festival (May 15-June 1) showcasing his 15 symphonies, numerous works for chamber ensembles, and a staging of his pivotal opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk.

Under the musical direction of Andris Nelsons, the Leipzig Shostakovich Festival divided the orchestral works between the two orchestras that he helms—the Leipzig Gewandhaus and the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO)—with the help of a special festival orchestra comprising youthful members of the Mendelssohn Orchestra Academy and the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra (between them, the latter delivered a rousing account of the Fifth Symphony under Russian conductor Anna Rakitina). A starry array of instrumental and vocal soloists plus the Quatuor Danel playing the 15 string quartets completed the lineup.

Andris Nelsons conducts the Boston Symphony Orchestra in Shostakovich symphonies

The locals got things off to a flying start with the Festive Overture ahead of a dynamic reading of the Second Piano Concerto. Indeed, so vigorous was Daniil Trifonov’s thrusting approach that the opening seemed to take the Gewandhaus Orchestra by surprise. Still, his determination to match the speeds adopted by Shostakovich himself was to be applauded. The highlight of the first concert, however, was a thrilling account of the Fourth Symphony. After a slightly hectic start that saw his foot pounding out the rhythm on the podium, Nelsons settled down to guide the audience through this sprawling, multifaceted work. To judge from the tear he wiped away at the devastating conclusion, it was music that meant a great deal to the Latvian conductor, who grew up under Soviet-style communism.

Daniil Trifonov performs the Second Piano Concerto with the Gewandhaus Orchestra

The second evening saw the first of numerous standing ovations. The 11th Symphony is played far less often than it deserves, and the BSO did it proud. On this showing it displayed a tighter, more disciplined ensemble than the Germans—recording these works across the last decade with Nelsons paid dividends. The warmth and color in the 11th was breathtaking, not to mention the sheer breadth of the sound. The 8th was similarly impressive, Nelsons making an especial impact throughout, crafting each phrase for maximum effect and wringing every drop of emotion from Shostakovich’s profound meditation on the folly of war.

That detailed approach was apparent in the concertos as well, in particular the First Violin Concerto whose brooding string tones and subterranean sound world flickered with the stygian colors of contrabassoon, tuba, and bass clarinet. The soloist, Nelsons’s fellow Latvian Baiba Skride, gave a generous performance that never tipped over into showboating. French cellist Gautier Capuçon, rich and velvety of tone, was at his most poetic in the virtuoso First Cello Concerto, finding textures in this music at times glossed over by lesser mortals.

It was perhaps the unexpected gems that made the festival such a memorable affair. In the hands of the Bostonians, the 6th Symphony—a fine piece of music rarely heard these days—was a fizzy, 11 a.m. pick-me-up, ahead of a probing account of the enigmatic 15th. And though neither of Shostakovich’s piano sonatas are commonly played—indeed, the unloved and often aggressive first requires fingers of titanium—Trifonov’s performances were nothing short of breathtaking.

The Leningrad Symphony, in its day the composer’s most internationally acclaimed work, received a colorful, in-your-face performance with the Boston and Leipzig forces coming together to satisfy its manifold demands. In the ideal acoustic of the Gewandhaus, Nelsons’s detailed account was full of light, shade, and instrumental firepower.

Chamber music, songs

The chamber music was excellent on the whole. Nikolai Szeps-Znaider was technically accomplished in the Violin Sonata if rather glued to the score. He redeemed himself three days later, however, when, with Trifonov and Capuçon, he delivered a roof-raising account of the Second Piano Trio, and then, with Antoine Tamestit and Yun-Jin Cho, an equally life-affirming performance of the Piano Quintet.

The songs, spread across two evenings, could hardly have been better served. Elena Stikhina delivered hugely engaging accounts of the Five Satires and the esoteric Romances on Poems of Alexander Blok. With her wine-dark mezzo, Marina Prudenskaya was outstanding in the austerely beautiful Marina Tsvetaeva poems. Along with the elegant Bogdan Volkov, they went on to serve up a mercurial reading of From Jewish Folk Poetry. Alexander Roslavets was commanding if a tad stentorian in the Michelangelo Verses.

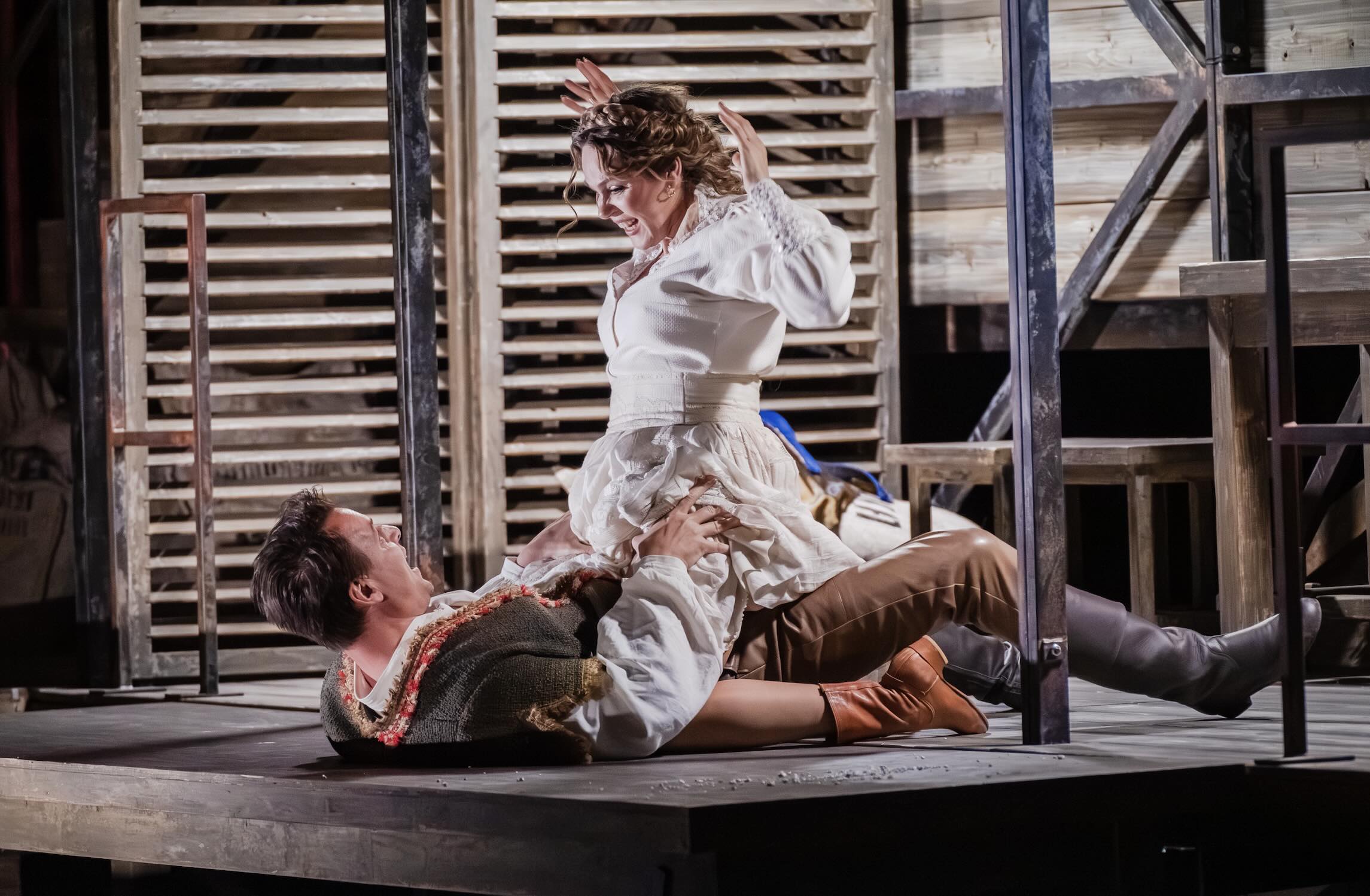

Kristine Opolais and Pavel Cernoch as Katerina and Sergei in Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk

Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk was presented in last year’s generally admired staging by Francisco Negrin. The direction needed more finesse at times, and it might have benefitted from a greater consistency of approach with respect to the opera’s satirical element, but visual shortcomings were overcome thanks to a moving central performance from Kristine Opolais as Katerina. The voice is less refulgent than it was, but hers was a deeply felt reading of a complex role. Pavel Cernoch was smoothly repellent as Sergei, Dmitry Belosselskiy vulgar and forceful as Boris, and all the minor roles were well taken. In the pit, Nelsons whipped up a storm—although he showed little mercy to his singers—and the super-sized chorus was especially fine.

Departing a few days ahead of the festival’s final performances meant closing with the 13th Symphony, Babi Yar. The work, once again, revealed itself to be Shostakovich’s masterpiece and the performance benefitted from a superb men’s chorus made up of members of three Leipzig choirs. Although Nelsons drove it hard at times, it was an overwhelming experience. The only fly in the ointment was Günther Groissböck who seemed insufficiently familiar with the language or the music, barely looking up from his music stand and coming momentarily adrift in the helter-skelter second movement.

All in all, this was an ambitious and thorough retrospective of a 20th-century great. Not only a chance to immerse oneself in the enormous range of his music but to reflect on the darkness and frequent horror of his life and times. A major achievement.

Photo credits: top 2 by Jens Gerber, bottom by Kirsten Nijhof

FEATURED JOBS

FEATURED JOBS

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO