Reviews

Adams's Antony & Cleopatra:

Misses the (Opera) Mark

John Adams’s works for the theater have typically shaded into oratorio. Nixon in China and The Death of Klinghoffer proceed less as dramatic narratives than as vehicles for librettist Alice Goodman’s poetic musings; similarly, Doctor Atomic, with its Peter Sellars texts assembled from sundry verbiage, is less a chronicle of the Manhattan Project than a contemplation of its moral ambiguity. But his Antony and Cleopatra is rooted in theater, its libretto drawn largely from Shakespeare’s play. The opera arrived at the Met on May 12, in San Francisco Opera’s 2022 world premiere staging—here cut by 20 minutes—by director Elkhanah Pulitzer.

John Adams’s works for the theater have typically shaded into oratorio. Nixon in China and The Death of Klinghoffer proceed less as dramatic narratives than as vehicles for librettist Alice Goodman’s poetic musings; similarly, Doctor Atomic, with its Peter Sellars texts assembled from sundry verbiage, is less a chronicle of the Manhattan Project than a contemplation of its moral ambiguity. But his Antony and Cleopatra is rooted in theater, its libretto drawn largely from Shakespeare’s play. The opera arrived at the Met on May 12, in San Francisco Opera’s 2022 world premiere staging—here cut by 20 minutes—by director Elkhanah Pulitzer.

Despite its Shakespearean backbone, the work did not demonstrate that Adams has developed into a bona fide opera composer. His music, both vocal and instrumental, is typically borne forward by persistent ostinatos. These lend his scores an unusual degree of coherence: He is able to present long-form structures lucidly and excitingly. But, on the evidence of Antony and Cleopatra, his compositional method remains inimical to the form of opera.

As in so much contemporary opera, Antony’s musical action is in the pit, with the singers picking out more or less arbitrary vocal lines above the pulsing orchestra. The composer, serving as conductor at the Met premiere, compounded the problem through balances that privileged the pit over the stage: Although the able singers were miked—standard practice in Adams’s vocal works—the voices often emerged as subsidiary. And even if they had been given a more prominent place in the aural image, they still would have struggled to convey the drama in the piece. Its score is singularly lacking in event, the pulsing momentum burying the contours of the theatrical moment. The opera proceeds smoothly but dispassionately, and the denouement, with the death of the tragic lovers, provides no pathos and no discernible catharsis. Shakespeare’s drama can’t take hold: It slides off the score.

Pulitzer’s production is efficient, while seldom achieving real theatricality. Dark panels dominate Mimi Lien’s set designs; these open and shut to create apertures for various scenes, but the prevailing monochrome undercuts any sense that we are witnessing ancient splendors. The lion’s share of the scenic depiction falls to Bill Morrison’s projections.

The scenic elements, along with Constance Hoffman’s costumes, place the action in the World War II era. Caesar’s Rome becomes Mussolini’s; his troops, the fascist army. The contemporary trope of setting nearly any opera with political content (Fidelio, Tosca, La forza del Destino) amidst the Axis forces of World War II has long since worn out its welcome; here the analogy seems especially lazy: Antony and Cleopatra fight Rome not to combat fascist oppression, but in the hope of asserting their own hegemony.

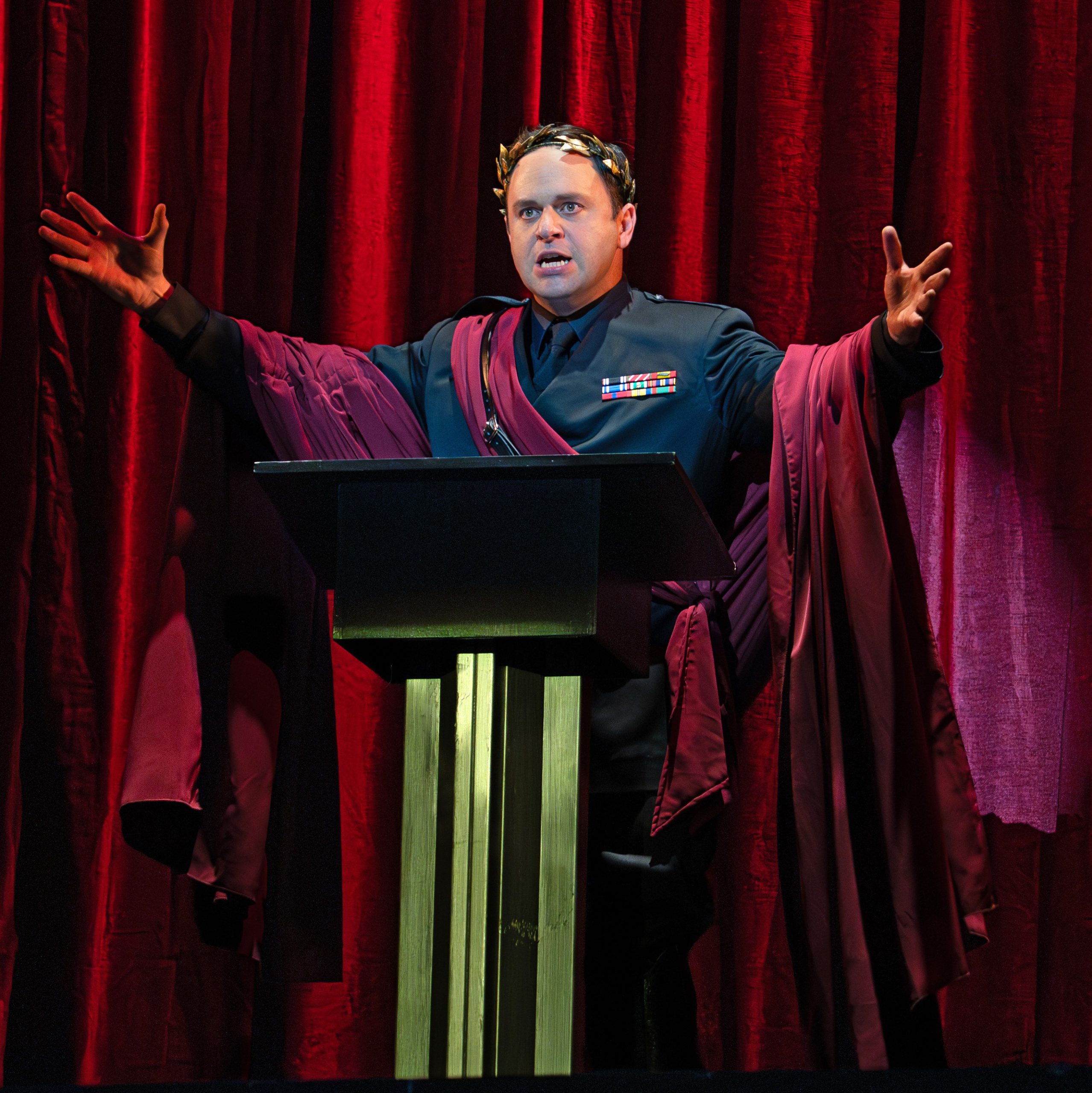

Cleopatra's Court, with Paul Appleby (right), as Caesar in John Adams's Antony & Cleopatra at the Met

The depiction of Cleopatra’s court as a kind of Hollywood fantasy is more successful. Enobarbus’s paean to the queen on her barge elicits Morrison’s happiest invention: a burnished image of the queen (Julia Bullock) that might well have been shot by George Hurrell, golden-age photographer of the stars. The description of Cleopatra “o’erpicturing—Venus” here seems particularly apposite.

The cast is an assemblage of remarkable performers, all particularly gifted in the singing of English text. Gerald Finley plays Antony. In the first-night performance, his bearing and verbal inflections went a long way toward providing the characterization lacking in the music itself. The warrior’s nobility and his human frailty both became tangible. The Canadian bass-baritone is four decades past his professional debut; during that time he has maintained a consistent and astonishing level of artistry and commitment to his craft. Meanwhile, the voice retains its solidity and handsomeness: This was the singing of an artist in his prime.

Bullock’s vocal estate was more problematic. Her soprano in its lower reaches exhibited its familiar dark allure. But her top sounded perilously unsupported. Bullock had been slated to sing the work’s world premiere but withdrew due to pregnancy. Her Met performance raised the question of whether Adams had written the role for her voice of several years ago, rather than the one she now has at her disposal. Nonetheless Bullock, a beautiful woman, was an ideal physical embodiment of the legendary monarch, and she was particularly adept at depicting the queen’s mercurial shifts in mood.

Bullock’s vocal estate was more problematic. Her soprano in its lower reaches exhibited its familiar dark allure. But her top sounded perilously unsupported. Bullock had been slated to sing the work’s world premiere but withdrew due to pregnancy. Her Met performance raised the question of whether Adams had written the role for her voice of several years ago, rather than the one she now has at her disposal. Nonetheless Bullock, a beautiful woman, was an ideal physical embodiment of the legendary monarch, and she was particularly adept at depicting the queen’s mercurial shifts in mood.

Tenor Paul Appleby cut an ignoble figure as Caesar, less the majestic ruler than a petty martinet. His bearing was thoroughly justifiable within the dramatic scheme of the piece: Octavius is, after all, Antony’s villain, his actions often characterized by vindictiveness. Appleby sang beautifully: his vocal lines musically shaped with every word of the text tangible.

Alfred Walker, through his genial bearing and the warmth of his bass-baritone, made Enobarbus’s compassion palpable. Mezzo Elizabeth DeShong was the sympathetic Octavia. Cleopatra’s handmaiden Charmian proved an effective debut vehicle for Taylor Raven, revealing a contralto-ish mezzo-soprano of impressive resonance. Other standouts included tenor Brenton Ryan, as Antony’s follower Eros; baritone Jarrett Ott, in his Met debut as the Roman triumvir Agrippa; and mezzo Eve Gigliotti, as Cleopatra’s attendant Iras. The discreet sound design was the work of Mark Grey, the field’s unquestionable doyen.

Top: Gerald Finley and Julia Bullock as Antony and Cleopatra

Bottom: Paul Appleby as Caesar

Photos: Karen Almond / Met Opera

FEATURED JOBS

FEATURED JOBS

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO