© Matt Crossick, PA Wire

The tsunami has struck and we are flattened in its wake. Humbled, even. So, now what? Pick up the remnants of the past and hammer them back together? Leave the debris behind and move on? Create a new model or fix the old?

“We need to build a bigger bridge to other kinds of musical worlds,” says composer David Lang. “What do we want to see? Who do we want to see in our audiences? What is the music we want to hear next to Bach, in dialog with Beethoven? What is the kind of social environment in which everyone will feel welcome to participate?”

Calling it “classical music” is part of the problem, he says. “We’ve been very protective of this bubble we call classical music—the way we teach it, the way we think about it, the way we train people to become a part of it, both as performers and listeners—all that separation needs to be questioned and challenged.”

In conversations with some of the field’s boldest and brightest, all are in agreement that the barriers we have built to the music we make—be they philosophical, socioeconomic, or pedagogical—have to go. “In the 20th century we’ve so imagined music through an institutional lens,” says director Peter Sellars, who has long argued the unsustainability of large institutional presenters. “The COVID crisis has made everybody step back from that and think more intimately. We forget that, 450 years ago, music operated in all kinds of other ways; small groups of people enjoying music is really the history of the art.”

He points to the proliferation of new chamber operas as an encouraging sign. “Composers are coming up with new opera experiences every week, but they’re only for a handful of people. And that sense of experimentation is wonderful and liberating; it doesn’t carry the heaviness of a large institutional product. Rather than stuffing something new down the throats of millions of people, let it come into the world with the few people who want it to. Let the excitement spread in a beautiful, natural way and not through a marketing campaign.”

Of babies and bathwater

All well and good, but there are a few practical considerations. While admitting that the pandemic has been a “huge wake-up call” for institutions to trim their sails and be better at saving for a rainy day, John Gilhooly, artistic and executive director of the Wigmore

Hall, argues, “We’ve got to save our institutions. Artists need them.”

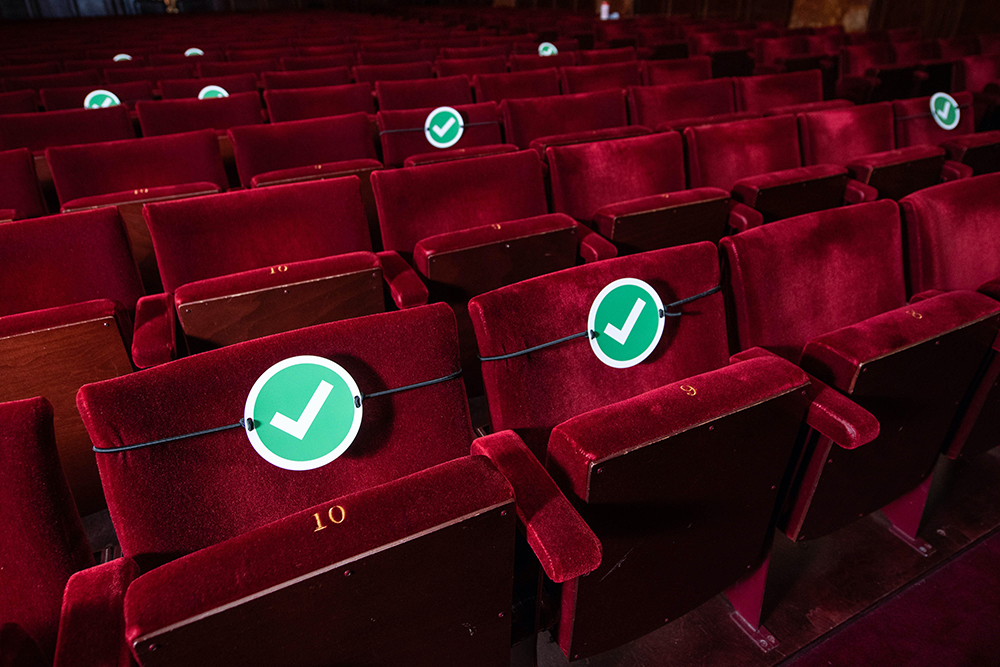

Wigmore, London’s favored chamber-music venue, was among the first to come back to life, bringing artists like pianist Stephen Hough into the hall last June to perform for an audience of none and live streaming the results. Building on that success, Wigmore has moved to a hybrid model for fall, presenting 100 chamber concerts for an audience of 56—just ten percent of the hall’s capacity—and, through its longstanding arrangement with the BBC, streaming or broadcasting each one. As restrictions lift, the audience size

can increase. “We are determined to get artists working again,” says Gilhooly, “and to pay them their full fees.”

Which brings up another, vital issue for the future, and that is the force majeure, or “act of God,” clause in most standard contracts, which enabled presenters earlier this year to cite the pandemic as cause to break agreements with thousands of contracted soloists, leaving the latter high and dry. The model of diplomacy, soprano Angel Blue—she of last season’s Bess fame at the Met—offers, “There are things in soloists’ contracts that are not conducive to a successful career. And when I say successful, I’m not talking about fame. I’m talking about just being able to make a living. I hope everyone takes away from this time the need to understand the other side, the need for the hierarchy in opera to begin to break down.’’

Breaking the barriers within

In the U.S. at least, the silos that separate performer from management, soloist from chorister or instrumentalist, union chief from the rank and file, are complicated, delicate, and long-held. While Gilhooly suggests every institution become its own broadcaster (“It’s not that difficult. You put your content up—be it educational or core programming or both—and [eventually] you can fill your halls”), for most U.S. institutions, that is a union issue. As of this writing, no one really knows how unions governing the work rules of performers and artistic staff are going to respond to what seems to be a universal desire—not to mention need—to scale back in size, scope, and, inevitably, salaries.

“There are going to be some union members who don’t want change,” says Kim Noltemy, president and CEO of the Dallas Symphony since 2018, and before that chief operating and communications officer of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. “They may want it to be the way it was before. But it can’t be the way it was before. If we’re going to succeed, we have to be about more than just a great concert. We have to be part of our audience’s lives, more a part of the community. Musicians need to understand that. This is a chance for all of us to

reset our relationships.”

It would appear that the DSO musicians—still all on full salary as of this writing—have been doing just that, performing some 40 concerts in small ensembles outdoors for patrons in lockdown and indoors in Meyerson Symphony Hall as early as June. “There was just this kind of enthusiasm to do whatever it takes to get in front of an audience, despite the conditions, the acoustics,

etc.,” says Noltemy.

Players who are uncomfortable leaving their homes have been participating in other ways, including calling patrons just to check in or teaching virtual lessons to the hundreds of underserved children in the DSO’s after school Young Musicians initiative, the goal of which is for every child to have free access to an instrument, lessons, and performances.

Technology to the rescue?

Perhaps technology is the answer—or at least one of them. Most presenters report large numbers of new audience members post-pandemic, reached through online efforts. Beth Morrison says technology has enabled presenters to “democratize the artform… because all people have to do is tune in.” By way of example, she sites Beth Morrison Projects’ production of Angel’s Bone, by Du Yun and librettist Royce Vavrek, scheduled for staging last spring by the LA Opera. When it was cancelled, the company put a video of a past production online. “If we had done it in person, about 2,000 people would have seen it,” says Morrison. “Instead, 20,000 people saw it!”

Soprano Angel Blue, who, as a onetime beauty pageant regular admits to being drawn to the showbiz aspects of her artform, says her colleagues need to “embrace” the media. “We have to be entrepreneurs in this moment,” she says. Certainly she is one. In March, she launched her own talk show, Faithful Friday, on her Facebook page, interviewing the likes of Christine Goerke, actor Laverne Cox, and chef Cat Cora. After a successful two-month run, she took a well-earned break before starting the series up again in the fall. She has also launched a vocal coaching series and plans to record and stream vocal selections from the two roles she was in the process of learning when the lockdown struck: the title role in Aida and Leonora in Il Trovatore.

As to racial barriers within her artform, she cites the Golden Rule and quotes her late father. “He always told me Angel, are you going to get better or are you going to get bitter?” She did, however, report that when she first moved to New Jersey from California, she was frequently stopped by police. Her husband, driving the same car, was not. He is white.

So, where does that leave us? “There’s going to be a huge struggle,” says Lang, “between the people who want to go back to where we were and the people who say we need to move forward and recognize that we’ve been changed. We’ve built these institutions to remind us where classical music has been. Now we need to think about where it can go.” •

Susan Elliott joined Musical America in 1999 and is its news & special reports editor. Previously, she was a contributor to the New York Times, Dance Magazine, Symphony, Opera News, and others. A pianist and composer by training, Elliott is a onetime arts critic for the Atlanta Journal Constitution and current treasurer of the Music Critics Association of North America.