NETWORK

NETWORK

Musical America has developed the most advanced search in the international performing arts industry. Click on the tabs below to identify the managers, artists, presenters, businesspeople, organizations and media who make up the worldwide performing arts community.

Management companies that advertise in the print edition have a hyperlink to their Artist Roster.

(If you would like to advertise in the Directory and receive the benefit of having your roster appear in this database, please click here.)

Choral Groups

Dance Companies

Orchestras

International Concerts & Facilities Managers

US/Canada Facilities

US/Canada Performing Arts Series

Festivals

Record Companies

1961 Rose Ln.

Pleasant Hill, CA 94523

(925) 689-3444

Reviews

Met's Flute Fanciful but Lacks Depth

A miniature Mozart festival has burst forth in the final weeks of the Metropolitan Opera’s season, with two new productions appearing in as many weeks, each staged by a debuting director from abroad who is better known here for work in theater than opera, and each conducted by French contralto, Nathalie Stutzmann, whose second career on the podium of late has become more prominent. Like its immediate Met predecessor, Don Giovanni, staged by Ivo van Hove, the new production of Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) by Simon McBurney is a recreation of a prior production, in this case, for the English National Opera in 2013. It opened Friday evening (May 19).

A miniature Mozart festival has burst forth in the final weeks of the Metropolitan Opera’s season, with two new productions appearing in as many weeks, each staged by a debuting director from abroad who is better known here for work in theater than opera, and each conducted by French contralto, Nathalie Stutzmann, whose second career on the podium of late has become more prominent. Like its immediate Met predecessor, Don Giovanni, staged by Ivo van Hove, the new production of Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) by Simon McBurney is a recreation of a prior production, in this case, for the English National Opera in 2013. It opened Friday evening (May 19).

If the Met scored a triumph with Don Giovanni, the result this time is considerably more mixed. McBurney, who is also an award-winning actor and playwright, co-founded the experimental theater company Complicité, and in Zauberflöte theatrical experimentation is part of the show. The stage is a blackbox affair, with scaffolding in view and a workplace stationed on each side of the proscenium, staffed by someone, rather like the Wizard of Oz, who implements technical aspects of the production, such as writing chalk labels on a blackboard for projection, or gives the illusion of doing so. Sound effects are prominent, from the noise of thunder to the gurgling of a swig of wine. Adding to the humor are imitations of Papageno’s birds by numerous extras, who wave folded pieces of paper and pretend they are wings.

During the close of the Pamina-Papageno duet, “Bei Männern welche Liebe fühlen,” a thunderstorm detracts from the music while the two seek shelter under a plastic umbrella. Usually the sound effects come during the opera’s spoken dialogue or during little inserted passages, such as those that rather graphically depict Tamino and Pamina’s trials of fire and water, which supplement the brief instrumental passages Mozart’s supplied for these episodes.

MET Orchestra's Bryan Wagorn plays the glockenspeil for Papageno (Thoms Oliemans) et al.

One added insert comes at Pamina’s initial appearance, as she desperately tries to elude capture by Monastotos and his men—a chilling moment that reinforces the opera’s serious dimension. Much of the action takes place on a suspended platform (Michael Levine designed the sets), which sometimes facilitates bilevel action and at other times is steeply raked, as if to emphasize the predicament of the characters. Nicky Gillibrand’s colorful, modern-dress costumes contrast with a stage that is mainly dark and unadorned, enhanced by darkish projections (by Finn Ross), some depicting a starry nocturnal sky, perhaps inspired by an early production of the opera.

Sarastro, plainly dressed and with long hair, and his followers, wearing suits and ties, seem surprisingly bland as they occupy a large conference room. Their opposition is led by an aged Queen of the Night, who needs a wheelchair (symbolic of her outmoded, pre-Enlightenment outlook, perhaps, but if she's so old, how can she sing those high F's?); the three boys she assigns to protect Tamino are decrepit old men. In a heartwarming moment at the end, the Queen is forgiven, rather than destroyed, and joins in celebrating Tamino and Pamina’s triumph, but otherwise the close is oddly inconclusive.

The Magic Flute, with its about-face of plot, Masonic elements, and detachment from an established literary tradition (apart from other singspiels given at Vienna’s Theater auf der Wieden), is difficult to come to terms with. McBurney keeps the audience involved with the drama and supplies lots of laughs, including one of a conspicuously scatological nature. Most of his innovations, peripheral though they often are, seemed geared to achieving this result. And the audience was enthusiastic, regardless of what the production left unsaid about the opera’s deeper mysteries. Still, some of the opera's humanity is lost to McBurney's cleverness.

The Magic Flute, with its about-face of plot, Masonic elements, and detachment from an established literary tradition (apart from other singspiels given at Vienna’s Theater auf der Wieden), is difficult to come to terms with. McBurney keeps the audience involved with the drama and supplies lots of laughs, including one of a conspicuously scatological nature. Most of his innovations, peripheral though they often are, seemed geared to achieving this result. And the audience was enthusiastic, regardless of what the production left unsaid about the opera’s deeper mysteries. Still, some of the opera's humanity is lost to McBurney's cleverness.

For the record, traces of Monastotos’s (Black) race have been removed from the text, as have its misogynistic references. In Act 2, the trio “Soll ich dich teurer nicht mehr sehn” was moved to the beginning of the act in place of the little duet for the priests.

Lawrence Brownlee’s glorious tenor, sounding as mellifluous as ever, invigorated Tamino’s lyrical music, but the singer was also telling in the accompanied recitative with the Speaker Priest, in which Tamino’s views about Sarastro are called into question. Although the role is often cast with a somewhat larger voice, Erin Morley’s silvery soprano sounded exquisite in Pamina’s music, not least in her melting account of “Ach, ich fühl’s.” Kathryn Lewek, an excellent Queen of the Night in every respect, was especially noteworthy in the slow section of her first aria, which had an uncommon degree of pathos as the Queen told of her grief over the abduction of Pamina. Thomas Oliemans, in his Met debut, was a lively if small-voiced Papageno, who carried a stepladder wherever he went. Bass Stephen Milling was more expressive than imposing as Sarastro. Stutzmann presided over a satisfying reading of the score characterized by fleetness and buoyancy. The orchestra pit is raised for this production, apparently to allow for closer involvement by the players in the action.

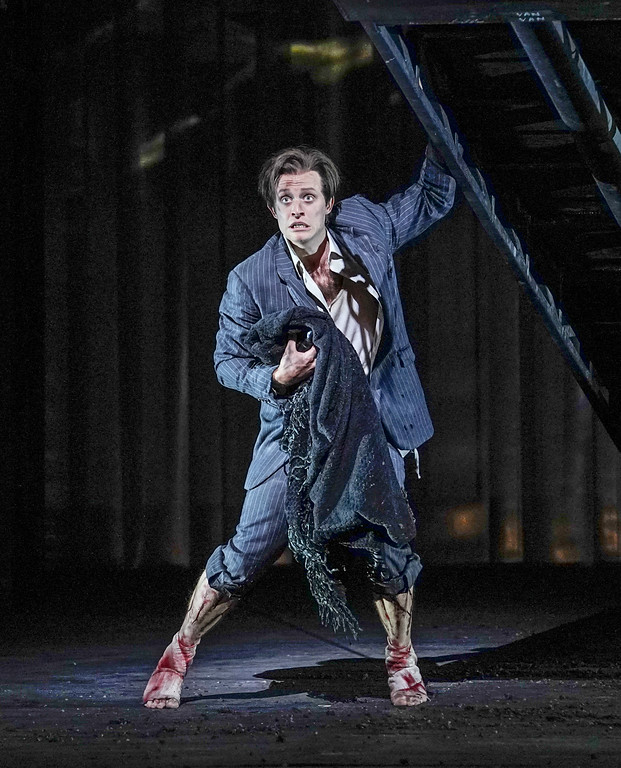

Top: Lawrence Brownlee as Tamino and Erin Morley as Pamina

Bottom: Brenton Ryan as Monastatos

Photos by Karen Almond/Met Opera

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO