By ANDREW POWELL

Published: February 22, 2017

MUNICH — Bavarian State Opera had a delicate problem. It was selling too many tickets online, more with each passing season. Its system, powered by CTS Eventim, was so robust and so fast that little was left to sell via phone or in person minutes after the 10 a.m. start time on heavy-demand days, causing embarrassment and a sense of unfairness inside its bricks-and-mortar box office, the Tageskasse, off chic Maximilianstraße.

No longer. This season, Germany’s busiest, richest, starriest and arguably best-managed opera company has a cure, one to make any Luddite proud. It does not smash the machines exactly. It instead decries the good system behind them and handicaps the online buyers who use them — seriously, unpredictably, before breakfast. BStO seats below €100 when Anja Harteros or Jonas Kaufmann sing are now all but inaccessible online.

“CTS Eventim’s system sometimes was not up for the amount of people trying to get tickets,” the company claimed in a late-January statement, and buying was “a bit of a lottery.” The system “would throw you out of the purchase process before ending it, which was acceptable neither for the Staatsoper nor for our audience.” Imagine. Computers that sell 100 million tickets annually for 180,000 events get the jitters handling Anja or Jonas.

These flaws and a desire “to make the system more stable,” BStO’s story goes, led to its decision last fall to handicap online buying on certain mornings in 2016–17. How? A delay is “activated” when events in heavy demand go on sale, postponing the moment the buyer “gets access” to the online box office, called in German the Webshop (or occasionally Onlineshop). Phone and in-person selling, meanwhile, proceed as usual from the 10 a.m. start time.

Understandably the opera company has never announced the handicapping, and sources familiar with the Tageskasse scene say CTS Eventim’s system had nothing to do with the decision. The real motive, according to these sources, is to try to replicate online the speed of the physical line (queue) at the Tageskasse following years of grumbling from people who buy that way, and from staff too. A tug-of-war between Internet users and the bricks-and-mortar crowd has accordingly shifted in favor of the latter.

Out-of-town buyers are the worst hit, having fewer routes to tickets. Bavarians resident outside their capital city — it is the “state” opera after all — and fans of the renowned company as far away as East Asia and North America greatly rely on the Webshop.

The disadvantage is not new at BStO. Indeed the artificial online delays effectively bring to the main season the same narrow price availability for out-of-towners they have long experienced with BStO’s 142-year-old summer Munich Opera Festival. Tickets for the festival are first sold in snowy January in person only, and the lower four of eight price categories — roughly, seats below €100 for major performances — sell out this way when the biggest stars are scheduled, months before online ticketing starts.

Countless customers were surprised by the handicap on Jan. 12, 14, 18, 22, 30 and Feb. 2 while trying to buy tickets for Philipp Stölzl’s new production of Andrea Chénier, due March 12 and starring — gosh — both Harteros and Kaufmann. All performances were affected on those selling mornings, corresponding to BStO’s two-month lead time.

Surprised, and confused actually. The handicap throws up two screens in place of the Webshop. First, a countdown page, labeled with the quaint metaphor “waiting room” to dupe people into thinking the system is too burdened to process their order. This assigns a wait number, which ironically turns out to be far from “stable.” Then comes a standby page, for buyers whose number has dropped to 0 (zero) before the Webshop opens, i.e. before 10 a.m. — a strange situation, one might think, but the only one with potential to yield broad ticket choice.

Not-so-hypothetical scenarios:

| |

A in Augsburg

Unaware of the handicap, she logs on at 9:55 a.m. She faces not her expected Webshop but the countdown page. (She would be there regardless of what event and date she is pursuing. The whole operation is impacted that morning because one heavy-demand performance is going on sale.)

She has of course no idea when the handicap was activated. (The answer could be 6 a.m., about when a physical line might start outside the Tageskasse.) But she is less troubled than buyers who may have purposefully stopped work in Tokyo or climbed out of bed in Boston.

She sees 29 lines of precise instructions auf Deutsch, unless she has opted for English screens, in which case she sees a remarkably compressed version of just five lines. (The complete English is here.) Key instruction: “Do not refresh.” Below, she reads her wait number: a high one, 400. Her chances are nil, but she doesn’t know this. She ties herself up for an hour before learning. |

| |

N in Nuremberg

Logs on at 5:55 a.m. She is too early and goes straight into the normally functioning Webshop. She assumes she can just wait there until 10 a.m. But no. She must refresh the screen every twelve minutes or be disabled for inactivity. No instructions say this because the system was in normal mode when she entered. (To see them, she would have had to arrive via the countdown page and witness her wait number drop to 0 before 10 a.m.)

When she casually returns to the screen at 9:30 a.m., she discovers the Webshop inactive for her. She reloads. Now she is on the countdown page with number 200. Again no chance. |

| |

R in Regensburg

Fares better. He logs on at 6:15 a.m., apparently just after the handicap was activated. He lands on the countdown page with number 10. Like A, he is told not to refresh. He obeys. Later, but before 10 a.m., his number drops to 9, then 7. He wonders how this could be. No orders are being processed. (Possible answer: people on the standby page are failing to refresh and losing their place.)

But for him to succeed, his number must drop to 0 by 10 a.m. Otherwise, whether he’s at 400 or 4, he will be stuck on the countdown page during the crucial initial selling minutes.

Luckily he does drop to 0. He is moved to the standby page, a promising but precarious place. There he sees the instruction to refresh that N missed. He must do this every twelve minutes until 10 a.m. If he has arrived on the standby page early, say at 7:15 a.m., he will be doing a lot of refreshing. Should he fail — just once — he will find himself back on the countdown page holding a high number. (Anja and Jonas never wanted it that way.)

When the hour rolls around and the handicap ends, he must be ready, as in the past, to point and click with decisiveness and accuracy. His seats are secure only when they appear in his Einkaufswagen, the shopping cart. |

A, N, and R may be imagined. The following numbers are real, recorded during the Jan. 18 handicap on Andrea Chénier ticketing in checks using two browsers and two connections:

Logging on at 10:24 a.m., a wait number of 688 with 170 seats left to sell. Three minutes later, wait number 346 with 130 seat left. At 10:43 a.m., number 179 with 38 seats. At 10:54 a.m., number 40 with 19 seats. After another five minutes, access to the Webshop with 4 seats shown as available. By 11:04 a.m., 2 seats left but neither one of them moveable into the shopping cart. At 11:07 a.m., sold out, Ausverkauft. Despite this, a new buyer could log on at 11:10 a.m. and receive wait number 382, which would drop to 0 six minutes later and lead to an empty Webshop.

Bavarian State Opera should end this nonsense. The company is damaging its reputation and working against its own carefully evolved ticket structure and sales procedures, designed to draw people of all income levels from a broad geography.

Those procedures sell tickets three ways: subscription; single-event by written order; and single-event by immediate fulfillment. The latter two are processed on a staggered basis according to performance date. Written orders (traditional mail, fax, email) are worked three months out. Immediate-fulfillment sales (online, phone, physical presence in the Tageskasse) begin two months out.

Each single-event method draws on fixed set-asides, or Kontingente, of seats in the 2,100-seat National Theater. These are broken down across BStO’s eight price categories and to within specific seating blocks, to as few as two seats, allowing near-total price and seat choice for each method. Quite sophisticated. And really quite fair, at least in the case of written orders. Even without handicapping, though, buyers outside Munich have less access to the immediate-fulfillment set-asides: getting to the Tageskasse may not be possible, and phoning is hard when there is heavy demand. Naturally they depend on the Webshop — and their hot connections, firm wrists, pinched fingertips and nanosecond nerves.

CTS Eventim, far from warranting criticism, could be held up as a most capable and user-friendly ticketer. Certainly its system offers an easier buyer interface, more precise seat sectioning, and lower fees, than that of the larcenous near-monopoly Stateside.

Instead of blaming its vendor, the opera company needs to go back to the future and solve its delicate Tageskasse problem with rigor and honesty. This means two things: adjustments to the Kontingente to reasonably protect in-person buyers; and an announcement of the change. Any tactic resulting in Internet screens that mislead buyers and waste their time, or too weird to spell out in a news release, is a bad one.

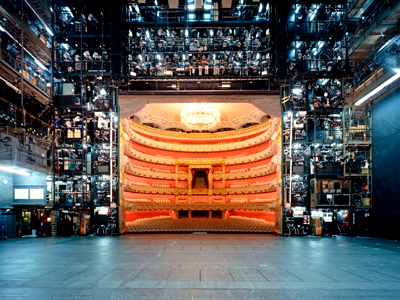

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Staatsoper Imposes Queue-it

Harteros Warms to Tosca

Antonini Works Alcina’s Magic

Portraits For a Theater

Staatsoper Objects to Report

Tags: Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Commentary, CTS Eventim, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, National Theater, Nationaltheater, News

This entry was posted on Wednesday, February 22nd, 2017 at 7:26 am and is filed under Munich Times. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

Staatsoper Favors Local Fans

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: February 22, 2017

MUNICH — Bavarian State Opera had a delicate problem. It was selling too many tickets online, more with each passing season. Its system, powered by CTS Eventim, was so robust and so fast that little was left to sell via phone or in person minutes after the 10 a.m. start time on heavy-demand days, causing embarrassment and a sense of unfairness inside its bricks-and-mortar box office, the Tageskasse, off chic Maximilianstraße.

No longer. This season, Germany’s busiest, richest, starriest and arguably best-managed opera company has a cure, one to make any Luddite proud. It does not smash the machines exactly. It instead decries the good system behind them and handicaps the online buyers who use them — seriously, unpredictably, before breakfast. BStO seats below €100 when Anja Harteros or Jonas Kaufmann sing are now all but inaccessible online.

“CTS Eventim’s system sometimes was not up for the amount of people trying to get tickets,” the company claimed in a late-January statement, and buying was “a bit of a lottery.” The system “would throw you out of the purchase process before ending it, which was acceptable neither for the Staatsoper nor for our audience.” Imagine. Computers that sell 100 million tickets annually for 180,000 events get the jitters handling Anja or Jonas.

These flaws and a desire “to make the system more stable,” BStO’s story goes, led to its decision last fall to handicap online buying on certain mornings in 2016–17. How? A delay is “activated” when events in heavy demand go on sale, postponing the moment the buyer “gets access” to the online box office, called in German the Webshop (or occasionally Onlineshop). Phone and in-person selling, meanwhile, proceed as usual from the 10 a.m. start time.

Understandably the opera company has never announced the handicapping, and sources familiar with the Tageskasse scene say CTS Eventim’s system had nothing to do with the decision. The real motive, according to these sources, is to try to replicate online the speed of the physical line (queue) at the Tageskasse following years of grumbling from people who buy that way, and from staff too. A tug-of-war between Internet users and the bricks-and-mortar crowd has accordingly shifted in favor of the latter.

Out-of-town buyers are the worst hit, having fewer routes to tickets. Bavarians resident outside their capital city — it is the “state” opera after all — and fans of the renowned company as far away as East Asia and North America greatly rely on the Webshop.

The disadvantage is not new at BStO. Indeed the artificial online delays effectively bring to the main season the same narrow price availability for out-of-towners they have long experienced with BStO’s 142-year-old summer Munich Opera Festival. Tickets for the festival are first sold in snowy January in person only, and the lower four of eight price categories — roughly, seats below €100 for major performances — sell out this way when the biggest stars are scheduled, months before online ticketing starts.

Countless customers were surprised by the handicap on Jan. 12, 14, 18, 22, 30 and Feb. 2 while trying to buy tickets for Philipp Stölzl’s new production of Andrea Chénier, due March 12 and starring — gosh — both Harteros and Kaufmann. All performances were affected on those selling mornings, corresponding to BStO’s two-month lead time.

Surprised, and confused actually. The handicap throws up two screens in place of the Webshop. First, a countdown page, labeled with the quaint metaphor “waiting room” to dupe people into thinking the system is too burdened to process their order. This assigns a wait number, which ironically turns out to be far from “stable.” Then comes a standby page, for buyers whose number has dropped to 0 (zero) before the Webshop opens, i.e. before 10 a.m. — a strange situation, one might think, but the only one with potential to yield broad ticket choice.

Not-so-hypothetical scenarios:

Unaware of the handicap, she logs on at 9:55 a.m. She faces not her expected Webshop but the countdown page. (She would be there regardless of what event and date she is pursuing. The whole operation is impacted that morning because one heavy-demand performance is going on sale.)

She has of course no idea when the handicap was activated. (The answer could be 6 a.m., about when a physical line might start outside the Tageskasse.) But she is less troubled than buyers who may have purposefully stopped work in Tokyo or climbed out of bed in Boston.

She sees 29 lines of precise instructions auf Deutsch, unless she has opted for English screens, in which case she sees a remarkably compressed version of just five lines. (The complete English is here.) Key instruction: “Do not refresh.” Below, she reads her wait number: a high one, 400. Her chances are nil, but she doesn’t know this. She ties herself up for an hour before learning.

Logs on at 5:55 a.m. She is too early and goes straight into the normally functioning Webshop. She assumes she can just wait there until 10 a.m. But no. She must refresh the screen every twelve minutes or be disabled for inactivity. No instructions say this because the system was in normal mode when she entered. (To see them, she would have had to arrive via the countdown page and witness her wait number drop to 0 before 10 a.m.)

When she casually returns to the screen at 9:30 a.m., she discovers the Webshop inactive for her. She reloads. Now she is on the countdown page with number 200. Again no chance.

Fares better. He logs on at 6:15 a.m., apparently just after the handicap was activated. He lands on the countdown page with number 10. Like A, he is told not to refresh. He obeys. Later, but before 10 a.m., his number drops to 9, then 7. He wonders how this could be. No orders are being processed. (Possible answer: people on the standby page are failing to refresh and losing their place.)

But for him to succeed, his number must drop to 0 by 10 a.m. Otherwise, whether he’s at 400 or 4, he will be stuck on the countdown page during the crucial initial selling minutes.

Luckily he does drop to 0. He is moved to the standby page, a promising but precarious place. There he sees the instruction to refresh that N missed. He must do this every twelve minutes until 10 a.m. If he has arrived on the standby page early, say at 7:15 a.m., he will be doing a lot of refreshing. Should he fail — just once — he will find himself back on the countdown page holding a high number. (Anja and Jonas never wanted it that way.)

When the hour rolls around and the handicap ends, he must be ready, as in the past, to point and click with decisiveness and accuracy. His seats are secure only when they appear in his Einkaufswagen, the shopping cart.

A, N, and R may be imagined. The following numbers are real, recorded during the Jan. 18 handicap on Andrea Chénier ticketing in checks using two browsers and two connections:

Logging on at 10:24 a.m., a wait number of 688 with 170 seats left to sell. Three minutes later, wait number 346 with 130 seat left. At 10:43 a.m., number 179 with 38 seats. At 10:54 a.m., number 40 with 19 seats. After another five minutes, access to the Webshop with 4 seats shown as available. By 11:04 a.m., 2 seats left but neither one of them moveable into the shopping cart. At 11:07 a.m., sold out, Ausverkauft. Despite this, a new buyer could log on at 11:10 a.m. and receive wait number 382, which would drop to 0 six minutes later and lead to an empty Webshop.

Bavarian State Opera should end this nonsense. The company is damaging its reputation and working against its own carefully evolved ticket structure and sales procedures, designed to draw people of all income levels from a broad geography.

Those procedures sell tickets three ways: subscription; single-event by written order; and single-event by immediate fulfillment. The latter two are processed on a staggered basis according to performance date. Written orders (traditional mail, fax, email) are worked three months out. Immediate-fulfillment sales (online, phone, physical presence in the Tageskasse) begin two months out.

Each single-event method draws on fixed set-asides, or Kontingente, of seats in the 2,100-seat National Theater. These are broken down across BStO’s eight price categories and to within specific seating blocks, to as few as two seats, allowing near-total price and seat choice for each method. Quite sophisticated. And really quite fair, at least in the case of written orders. Even without handicapping, though, buyers outside Munich have less access to the immediate-fulfillment set-asides: getting to the Tageskasse may not be possible, and phoning is hard when there is heavy demand. Naturally they depend on the Webshop — and their hot connections, firm wrists, pinched fingertips and nanosecond nerves.

CTS Eventim, far from warranting criticism, could be held up as a most capable and user-friendly ticketer. Certainly its system offers an easier buyer interface, more precise seat sectioning, and lower fees, than that of the larcenous near-monopoly Stateside.

Instead of blaming its vendor, the opera company needs to go back to the future and solve its delicate Tageskasse problem with rigor and honesty. This means two things: adjustments to the Kontingente to reasonably protect in-person buyers; and an announcement of the change. Any tactic resulting in Internet screens that mislead buyers and waste their time, or too weird to spell out in a news release, is a bad one.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Staatsoper Imposes Queue-it

Harteros Warms to Tosca

Antonini Works Alcina’s Magic

Portraits For a Theater

Staatsoper Objects to Report

Tags: Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Commentary, CTS Eventim, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, National Theater, Nationaltheater, News

This entry was posted on Wednesday, February 22nd, 2017 at 7:26 am and is filed under Munich Times. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. Both comments and pings are currently closed.

Musical America Blogs is proudly powered by WordPress

Entries (RSS) and Comments (RSS).