By James Jorden

It may have been Robert A. Heinlein or Napoleon Bonaparte who first crafted that variation on Occam’s Razor “Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity.” But whoever said it, in whatever century and in whatever language, it certainly seems to apply to the fiasco that is the Deutsche Oper am Rhein’s Tannhäuser.

Not that we’re talking about the production per se here; no one really knows much about what really transpired onstage besides the first-night audience who actually saw seen it, minus that subset who slammed the doors on the way out of the theater and those mysteriously delicate Düsseldorfers whose exposure to imagery from the recent past landed them in the ER.

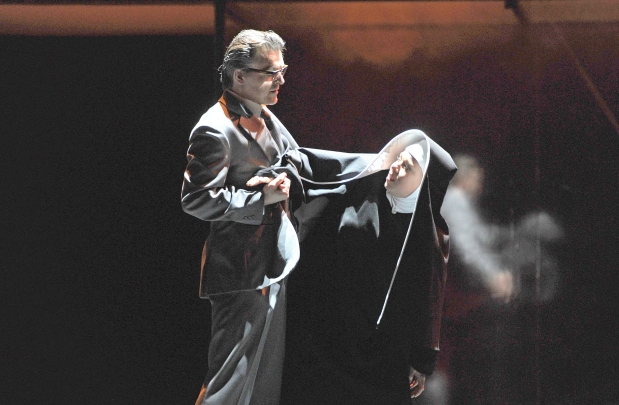

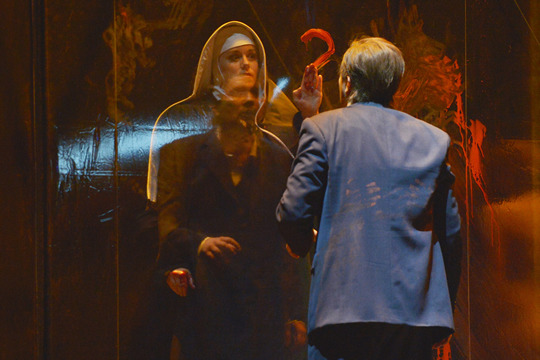

No, since the DO have taken the virtually unprecedented step of canceling the production after the first night, the vast majority of opera-watchers in the world have no way of gaining first-hand knowledge of what the production is like, and vanishingly little of second-hand. There’s no complete video, not even a trailer, and the company has released only a dozen or so fairly innocuous still photos. A TV news report offers a few seconds of dress rehearsal footage.

And the production will apparently never be revived.

Not that this lack of information has hampered armchair experts half a continent away from framing and expounding detailed exegeses of the production. For example, the cocktail of Wagner, the Holocaust and Regie proved irresistible catnip for Norman Lebrecht, who has spent the best part of the past week cheerleading for the banning of a production he has never laid eyes on.

But even serious journalists are running around with their hair on fire. In The Guardian, Kate Connolly placidly parrots the claim made by the DO’s press department that “some scenes, in particular the very realistically portrayed shooting scene, caused such strong psychological and physical reactions in some visitors that some of them had to be taken into medical care,” without bothering to ask how many “visitors” were so taken with vapors, or, more to the point, why exactly an opera company is receiving medical updates from members of the audience.

Unfazed by having no facts to go on, Connolly does what any crack British journalist does under the circumstances, which is to interview an Oxford academic who not only knows nothing about the particulars of the case but seems shaky on musical history as well:

This production rather hit the audience over the head with its message. It recalls the scenes in Ken Russell’s film Lisztomania, in which Wagner emerges from a Nazi grave at a Nuremberg-style rally and shoots everyone with a machine-gun-cum-electric guitar. While Wagner has questions to answer in relation to the Third Reich, a degree of subtlety would help.

Yes, subtlety is nice, but so is honesty. Did this James Kennaway see the production, and, if as it seems, he did not, what is he doing commenting on it?

So, since I know as little as everyone else, what follows is almost pure guesswork, with a few provisional conclusions based on the assumption that at least some of the hearsay floating around is correct.

This is Burkhard Kosminski’s first attempt at directing opera. He has a rather long resumé in straight theater, about 40 productions since 2000. Here, for example, is a trailer for his staging of August: Osage County.

The reviews for the opera, meanwhile, are most negative:

“Es ist eine schlechte, weil unsensible und unwürdige Inszenierung. Und das ist schade, weil das gesamte Ensemble eine überzeugende Leistung abliefert, die so nicht ausreichend gewürdigt wird.”

“Es ist ein Abend, dessen Wirkung man sich nicht entziehen kann – und der gleichzeitig, alsTannhäuser-Produktion betrachtet, ein szenisches Desaster und musikalisch über weite Strecken enttäuschend oder gar ärgerlich ist.”

And so far as I can make out from descriptions of the production, Kosminski’s big ideas mostly involve the first 45 minutes of the opera and the finale: during the overture, there is a graphic depiction of execution by lethal gas, and then, at a pause in the scene between Venus and Tannhäuser, the “hero,” apparently a passive stooge for the Nazis, shoots dead a husband, wife and child. Later, Elisabeth, who by the third act has taken the veil as a nun, is raped by Wolfram and then self-immolates, leaving a refugee child to hand an olive branch to the dying sinner.

Yes, it does sound rather heavy-handed and something of a mess. But, even stipulating that, should the staging have been canceled after the first night?

As a purely practical matter, perhaps. Taking so bold and unusual a step makes the management of the DO seem decisive and responsive to their audience, and it relieves them of the responsibility of having to defend a production that (for all we know) may indeed be a heavy-handed mess.

But the responsibility of a theater’s management is not solely to the public; it also needs to support its artists. Even artists who have failed–or, really, especially artists who have failed–need to be assured that the theater values them: you’re not evil, you’re not stupid; you just didn’t get it right this time around.

And the violation between intendant and artist is what really bothers me about the abrupt decision to cancel this Tannhäuser. The message the action sends is, “When the going gets tough, don’t count on us to stand by our artists. We will rather listen to whoever howls loudest among the mob.”

Ass-covering belongs in no art manifesto, in an opera house or anywhere else.

Photos: Hans Jörg Michel