Mobile and Live Performance: A Not Imperfect Union

By John Fleming

November 1, 2016

![]() Keeping your mobile device on during a live performance—or at least before, between, and after—is no longer strictly verboten. In fact, in some cases your personal mobile device can amplify and enhance the greater experience. Here are a few early adventures in the intersection between the live action under the proscenium and the screen action in your hand.

Keeping your mobile device on during a live performance—or at least before, between, and after—is no longer strictly verboten. In fact, in some cases your personal mobile device can amplify and enhance the greater experience. Here are a few early adventures in the intersection between the live action under the proscenium and the screen action in your hand.

Lincoln Center’s Field Trip to the Super Bowl

Last February, Lincoln Center’s Senior VP for Brand & Marketing Peter Duffin and several other staff members went t the Super Bowl—not because they’re necessarily football fans but because they wanted to observe Levi’s Stadium in action. Home of the San Francisco 49ers since opening in 2014, the Santa Clara, CA, facility is the most digitally connected stadium in the world, equipped with a staggering array of Ethernet, cloud-based voice, HD Wi-Fi, and broadcast technology. With their mobile devices, fans can do everything from order a drink at their seats to download and share exclusive in-venue content on social media. (PHOTO: Lincoln Center VP for Brand & Marketing Peter Duffin.)

Last February, Lincoln Center’s Senior VP for Brand & Marketing Peter Duffin and several other staff members went t the Super Bowl—not because they’re necessarily football fans but because they wanted to observe Levi’s Stadium in action. Home of the San Francisco 49ers since opening in 2014, the Santa Clara, CA, facility is the most digitally connected stadium in the world, equipped with a staggering array of Ethernet, cloud-based voice, HD Wi-Fi, and broadcast technology. With their mobile devices, fans can do everything from order a drink at their seats to download and share exclusive in-venue content on social media. (PHOTO: Lincoln Center VP for Brand & Marketing Peter Duffin.)

“They call it a BYOD stadium—bring your own device,” says Duffin. “I’m a big believer that those of us working in the not-for-profit space need to learn from people in the for-profit space in parallel industries—and sports definitely is one—who may have more resources at their fingertips.

“They call it a BYOD stadium—bring your own device,” says Duffin. “I’m a big believer that those of us working in the not-for-profit space need to learn from people in the for-profit space in parallel industries—and sports definitely is one—who may have more resources at their fingertips.

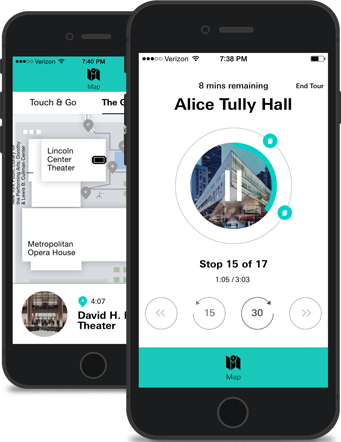

To that end, Lincoln Center now offers free public Wi-Fi throughout its 16-acre campus and provides a mobile app at certain of its venues that enables the user to pre-order intermission drinks or track the length of the rest-room line. There’s also an app with a tour of the center. (PHOTO: Lincoln Center tour app.)

High-tech hopes for Geffen

High-tech hopes for Geffen

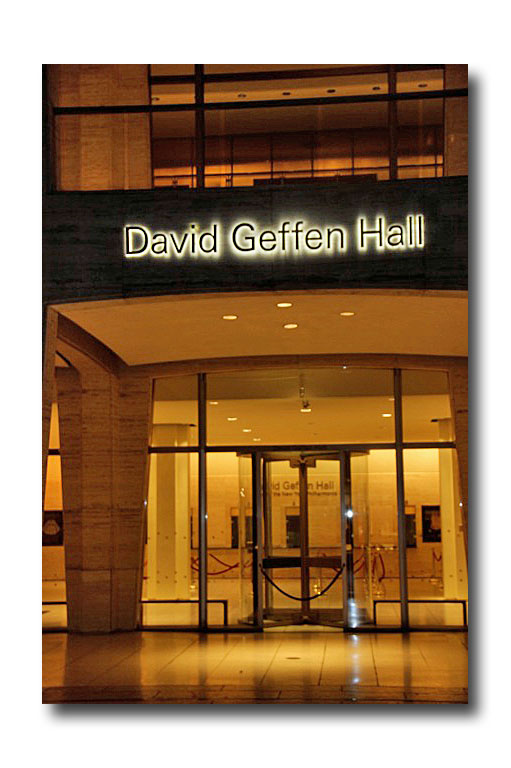

With Geffen Hall, home of the New York Philharmonic, scheduled to undergo a projected $500 million renovation starting in 2019, the building’s digital infrastructure will be a priority, though Duffin says it is still under development. “We want all of our venues to be very digitally enabled, but we don’t have a crystal ball. How do we build these buildings so they can enable whatever the technology is down the road? We talk a lot about making sure there are holes in the venues to facilitate whatever new wiring is going to be needed.”

Demographics is an urgent reason for the introduction of more technology into the performing arts, says Duffin. “Obviously, for younger generations, their experience of the world is mediated through their phone, and we have to meet that demand. Plus, there are things you can do with mobile technology that you really couldn’t do in any other way.” (PHOTO: A $500 million upgrade says Geffen Hall will be “very digitally enabled.”)

Nobody is posting selfies during New York Phil concerts—yet. “For us, we draw the distinction between what I call the doughnut around the performance, the pre- and post-performance space, and the actual performance,” Duffin says. “In sports, connectivity takes place constantly during the performance, but we try to keep the in-performance experience free of digital clutter. Our drink ordering shuts off when the show starts. We don’t want you to be playing with your phone. We want you to be focused on the stage.”

LiveNote in Philadelphia

For selected concerts, the Philadelphia Orchestra encourages audience members to keep their mobile devices on and download LiveNote, an app that provides program notes and other information in synch with the performance.

For selected concerts, the Philadelphia Orchestra encourages audience members to keep their mobile devices on and download LiveNote, an app that provides program notes and other information in synch with the performance.

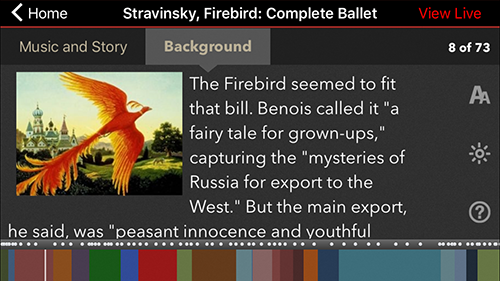

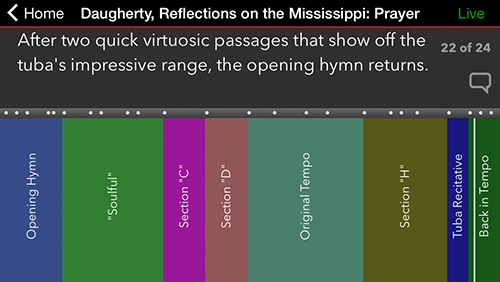

Developed by the orchestra in collaboration with Drexel University starting in 2011, at a cost of about $300,000, LiveNote is like having a slide show on your phone, with multiple options to guide you through a piece. There are several tracks from which to choose: one for a user with no music background that brings in historical and cultural references, another that is more specific to the score, explaining such aspects as thematic development, key change, instrumentation, motivic material, and so forth. A third track is geared to kids. Also available is an overall map of the music being played. (PHOTO: Philadelphia Orchestra’s LiveNote app provides program commentary in synch with performance.)

“Developing the content is the art form in this,” says Jeremy Rothman, the orchestra’s vice president for artistic planning. “You can have really slick technology, it can interface well with the concert, but if the content is just mediocre, then what’s the point?” (PHOTO: Philadelphia Orchestra VP for Artistic Planning Jeremy Rothman.)

“Developing the content is the art form in this,” says Jeremy Rothman, the orchestra’s vice president for artistic planning. “You can have really slick technology, it can interface well with the concert, but if the content is just mediocre, then what’s the point?” (PHOTO: Philadelphia Orchestra VP for Artistic Planning Jeremy Rothman.)

Ben Roe, a longtime public radio and TV broadcaster who is now executive director of the Heifetz International Music Institute, has created much of the LiveNote content. “The idea is that you have somebody sitting right next to you,” continues Rothman, “telling you at just the right moment what’s about to happen, or what to listen for. It’s like somebody tapping you on the shoulder and saying, ‘Coming up is one of the most famous oboe solos in the repertoire. Check it out.’ And then your hear it.”

LiveNote has been gradually introduced to audiences over the past two years. At several concerts in which it was available last season, about 18 percent of the audience downloaded it.

This season, LiveNote is being offered on eight subscription programs, for works such as Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloe, Orff’s Carmina Burana, the Shostakovich Fourth Symphony, Canteloube’s Songs of the Auvergne, Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle, and Mason Bates’s Alternative Energy.

Though LiveNote may be responsive to a younger demographic that constantly interacts with its smartphones, Rothman views the app primarily in artistic terms. “I don’t think this is so much about demographics. This is not a gimmick to get people interested in the orchestra. This is about enhancing the musical experience with the tools we have today.”

Solving the translation problem Rothman finds LiveNote especially useful for following text and translations for opera and oratorios. “Rather than there being a supertitle screen above the stage, you have the text in your hand,” he says. “I’m somebody who likes to see the original language and look at it next to the translation. You can’t do that with supertitles. You can do that with a printed program, but a program doesn’t track along with the music in real time. The other drawback of supertitles is that if you miss something, it’s gone, whereas with this app, you can flip back a couple of slides, read the translation of what was sung, then hit the live button to jump right back to where you are in the piece.” (PHOTO: LiveNote graphics use muted colors so the screens can be used anywhere in the hall.)

Rothman finds LiveNote especially useful for following text and translations for opera and oratorios. “Rather than there being a supertitle screen above the stage, you have the text in your hand,” he says. “I’m somebody who likes to see the original language and look at it next to the translation. You can’t do that with supertitles. You can do that with a printed program, but a program doesn’t track along with the music in real time. The other drawback of supertitles is that if you miss something, it’s gone, whereas with this app, you can flip back a couple of slides, read the translation of what was sung, then hit the live button to jump right back to where you are in the piece.” (PHOTO: LiveNote graphics use muted colors so the screens can be used anywhere in the hall.)

The app features a dark screen and grey lettering and graphics in muted colors. “Frankly, I find it less obtrusive than sitting next to somebody flipping pages in the playbill, or shining their penlight on the page to read the text in the dark,” says Rothman. The app is designed for use anywhere in the hall. “We worked hard to make it very subtle, very unobtrusive to somebody sitting next to you,” he continues. “Ultimately, we came to the conclusion that if we didn’t feel it could be everywhere in the hall, then it should be nowhere in the hall. We didn’t want to sequester people.”

Rothman calls LiveNote “a more personalized experience” and reports far less “blowback” with its use in the hall than with in-concert video. “Video is more in your face,” he says. “What we’ve learned in surveys,” says Ryan Fleur, vice president for advancement “is that people who have used the app either really like it or are neutral. Those who haven’t tried it tend not to like it. So the goal, the key, is to get it into people’s hands and let them try it. Because nobody who tried LiveNote hated it.”

In addition to the $300,000 in development and software costs, Fleur estimates the orchestra paid between $50,000 and $100,000 to equip Verizon Hall with Wi-Fi to operate LiveNote. “It’s a closed network, and once they’re on it, it’s difficult for people to check their email or go on Facebook,” he says. Other performing arts organizations have expressed interest in the app, which the orchestra is looking into licensing. “We’ve heard from about 40 organizations asking about LiveNote, ranging from the Royal Concertgebouw in Amsterdam to the Pensacola Symphony.”

Free iPads get mixed results in Boston

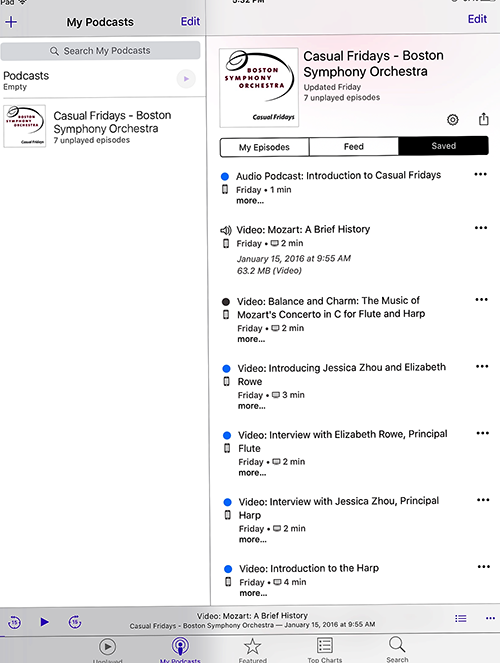

For three “Casual Fridays” concerts last season, the Boston Symphony Orchestra offered iPads pre-loaded with program notes, scores, and interviews with soloists. Ticket-buyers could use the devices in a 100-seat technology area at the rear of Symphony Hall that featured video monitors showing the conductor from the orchestra’s point of view. The conductor cam was popular, the iPads, not so much. ((PHOTO below: Boston Symphony orchestra Chief Operating and Communications Officer Kim Noltemy.)

For three “Casual Fridays” concerts last season, the Boston Symphony Orchestra offered iPads pre-loaded with program notes, scores, and interviews with soloists. Ticket-buyers could use the devices in a 100-seat technology area at the rear of Symphony Hall that featured video monitors showing the conductor from the orchestra’s point of view. The conductor cam was popular, the iPads, not so much. ((PHOTO below: Boston Symphony orchestra Chief Operating and Communications Officer Kim Noltemy.)

“We came to the conclusion that people didn’t want to use devices during concerts,” says Kim Noltemy, the BSO’s chief operating and communications officer. “Honestly, we found that people, other than using the iPad as a score reader, almost didn’t look at it at all during the concert. There wasn’t a lot of demand for it. We had 100 iPads available to start this off, and we never even had 100 requested.” The orchestra has discontinued the iPad project, although the conductor cam remains, viewable from 100 seats ($25 a piece) in a certain section of the hall. “There was incredible enthusiasm for that,” Noletmy says. “People were riveted.” (PHOTO: Menu options for Boston Symphony Orchestra Casual Fridays iPad experiment.)

“We came to the conclusion that people didn’t want to use devices during concerts,” says Kim Noltemy, the BSO’s chief operating and communications officer. “Honestly, we found that people, other than using the iPad as a score reader, almost didn’t look at it at all during the concert. There wasn’t a lot of demand for it. We had 100 iPads available to start this off, and we never even had 100 requested.” The orchestra has discontinued the iPad project, although the conductor cam remains, viewable from 100 seats ($25 a piece) in a certain section of the hall. “There was incredible enthusiasm for that,” Noletmy says. “People were riveted.” (PHOTO: Menu options for Boston Symphony Orchestra Casual Fridays iPad experiment.)

The Tanglewood Lawncast The BSO first experimented with using mobile devices during concerts in 2014, with a Lawncast at its summer home at the Tanglewood Music Center. Concertgoers could access content about the all-Dvorák program and live video on smartphones and tablets. “We had a designated area on the lawn, which we pushed pretty hard, but it was not popular at all,” Noletmy says. “I think maybe what could work at Tanglewood is more of social media kind of thing, something interactive.” But building the infrastructure for that would be incredibly expensive, says Noletmy. “With the trees and the wind and the weather, having a stable Wi-Fi connection on our lawn proved to be far more challenging that we anticipated.” (PHOTO: Screenshot from 2014 Tanglewood Lawncast.)

The BSO first experimented with using mobile devices during concerts in 2014, with a Lawncast at its summer home at the Tanglewood Music Center. Concertgoers could access content about the all-Dvorák program and live video on smartphones and tablets. “We had a designated area on the lawn, which we pushed pretty hard, but it was not popular at all,” Noletmy says. “I think maybe what could work at Tanglewood is more of social media kind of thing, something interactive.” But building the infrastructure for that would be incredibly expensive, says Noletmy. “With the trees and the wind and the weather, having a stable Wi-Fi connection on our lawn proved to be far more challenging that we anticipated.” (PHOTO: Screenshot from 2014 Tanglewood Lawncast.)

With a small staff, Noltemy outsources most of the BSO’s tech work. “The challenging part for all of us who are not technology companies is the process,” she says. “There’s nothing that comes out of a box. Whenever you do something it’s very time consuming and labor intensive. To launch a new app might take six to nine months. I can’t just go buy the software, spend a week filling in our content, and then it’s ready. Every bit of content has to be current. You can’t have anything old. Even an orchestra member’s bio is going to be invalid after one year because you have to update all the new and important things that have happened. I don’t think there’s a nonprofit in the country adequately staffed for what needs to be done today.”

The BSO has mixed feelings about the use of mobile devices during performances. “A lot of patrons are very much against it,” says Noltemy. “In surveys, at least 30 percent are strongly opposed. This is an organization that has existed for a really long time and lot of people are happy with the way it is. But of course we know that complacency is not good.”

Tweet seats at Opera Theater of St. Louis

“Tweet seats,” for people who do real-time Twitter commentary on a production, are not uncommon among opera companies. San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Minnesota Opera, LA Opera, and San Diego Opera are among those that invite tweeters to do their thing from a specific section of the theater—but only at dress rehearsals.

Opera Theater of St. Louis is rare, in that it has tweet seats during one or two actual performances, beginning in 2013 with The Pirates of Penzance. This past season, there was a Twitter stream for two performances of La Bohème at #otslboheme.

“A dress rehearsal is not a performance in terms of electricity and the polish of a performance,” OTSL General Director Timothy O’Leary says. “If we’re inviting the public to evaluate the performance and share that evaluation with their Twitter followers, we want them to be experiencing the real thing.” (PHOTO: Opera Theater of St. Louis General Director Timothy O’Leary.)

“A dress rehearsal is not a performance in terms of electricity and the polish of a performance,” OTSL General Director Timothy O’Leary says. “If we’re inviting the public to evaluate the performance and share that evaluation with their Twitter followers, we want them to be experiencing the real thing.” (PHOTO: Opera Theater of St. Louis General Director Timothy O’Leary.)

Opera Theater requires live tweeters to apply for the complimentary tickets (usually $50 to $89) and “demonstrate that they have a large enough following on Twitter,” O’Leary says. “It wouldn’t be worth our while to provide comps for someone who has 10 followers.” The numbers of followers for the 43 live tweeters during La Bohème ranged from 43 to 5,003.

The tweet seats are in two back rows of the 954-seat theater, with a buffer row between them and other audience members. Tweeters are told to use cellphones and not tablets or laptops, which emit more light, and the phones must be on silent. “Because they’re in the back of the center bay, you can’t see the tweeters from anywhere else in the house,” says Joe Gfaller, director of marketing and public relations. “They’re largely blocked off by the physical landscape of the theater. They’re not visible unless you’re really looking for them.” Gfaller says he has heard only one complaint about live tweeting in the four years it has been going on. (PHOTO: Group shot of OTSL La Bohème Twitter users; their followers ranged from 43 to 5,003.)

The tweet seats are in two back rows of the 954-seat theater, with a buffer row between them and other audience members. Tweeters are told to use cellphones and not tablets or laptops, which emit more light, and the phones must be on silent. “Because they’re in the back of the center bay, you can’t see the tweeters from anywhere else in the house,” says Joe Gfaller, director of marketing and public relations. “They’re largely blocked off by the physical landscape of the theater. They’re not visible unless you’re really looking for them.” Gfaller says he has heard only one complaint about live tweeting in the four years it has been going on. (PHOTO: Group shot of OTSL La Bohème Twitter users; their followers ranged from 43 to 5,003.)

Critics on the fly

Tweeters are treated like members of the press. “They get a press kit, and we allow them to download photos already approved for the press that they can use while they’re tweeting,” Gfaller says. “There

was only one time when someone broke the rules and took their own photo during the performance, and they quickly took it down and were very apologetic.”

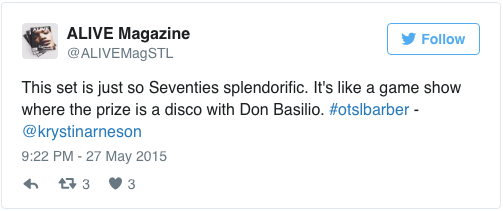

The Twitter stream has included as many as 1,200 tweets during a single performance. In 2014, the OTSL staging of The Magic Flute, directed and designed by famous fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi, even drew a response from Mizrahi himself. “Given Isaac Mizrahi’s reach on Twitter, that meant that hash tag #otslflute went out to tens of thousands of his followers very quickly,” Gfaller says. (PHOTO: Twitter commentary posted at hashtag #otslbarber during OTSL dress rehearsal.)

The Twitter stream has included as many as 1,200 tweets during a single performance. In 2014, the OTSL staging of The Magic Flute, directed and designed by famous fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi, even drew a response from Mizrahi himself. “Given Isaac Mizrahi’s reach on Twitter, that meant that hash tag #otslflute went out to tens of thousands of his followers very quickly,” Gfaller says. (PHOTO: Twitter commentary posted at hashtag #otslbarber during OTSL dress rehearsal.)

The cast is in on the act

Many singers are active Twitter users, and cast members often join the stream during intermission. In 2014, tenor Rene Barbera, singing Nemorino in The Elixir of Love, got into a Twitter conversation with one of the live tweeters, who was a volunteer at Kingdom House, a social service organization in St. Louis. “The end result was that during the run Rene visited Kingdom House to sing for a group of young people there,” O’Leary says. “A traditional performance would never have had the opportunity for something like that to happen.”

Opera Theater has stuck with standard repertory for live tweeting. “We’re drawn toward pieces that are comedies, that are visually compelling and that have a strong foundation in the pantheon of great opera,” Gfaller says. “The people coming to live tweet are more likely to be new operagoers themselves. They are less critics and more lifestyle bloggers.” Surprisingly, the tweeters have not necessarily fit the stereotype of tech-savvy youngsters. “I assumed it would mostly be Millennials, but in practice, we’ve had people into their 60s doing this.” O’Leary says it’s hard to measure the direct impact of the live tweeting on ticket sales. “The value of doing it is the tremendous capacity of Twitter and social media in general to create word of mouth and make the kind of impact that is less and less available

from traditional media coverage.”

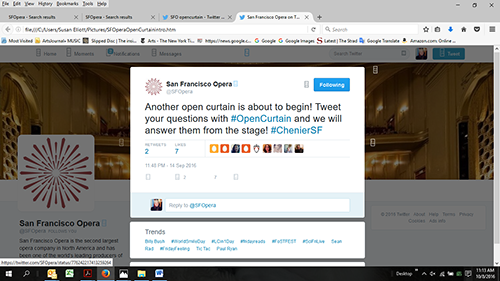

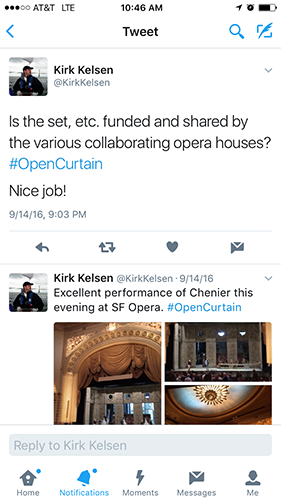

Twitter Q&A in San Francisco—cue the set change

Sometimes, the stage action between acts is as interesting as the performance. San Francisco Opera’s Open Curtain capitalizes on that, with the curtain remaining up at intermission at selected performances so audience members can watch the stage crew; people use a hashtag on Twitter to ask questions of the crew. (PHOTO: San Francisco Opera Open Curtain during recent Andrea Chénier intermission.)

Sometimes, the stage action between acts is as interesting as the performance. San Francisco Opera’s Open Curtain capitalizes on that, with the curtain remaining up at intermission at selected performances so audience members can watch the stage crew; people use a hashtag on Twitter to ask questions of the crew. (PHOTO: San Francisco Opera Open Curtain during recent Andrea Chénier intermission.)

For an Open Curtain during Andrea Chénier in September, Ted Schaller, the company’s digital content manager, fielded tweets from the audience on his phone and relayed questions to Daniel Knapp, the company’s director of production. “It was a particularly interesting set change because the stagehands were pulling chandeliers off the ceiling, tearing down walls, putting up new doors, setting up new tables,” Schaller says. “The stagecraft that goes on behind the scenes is almost more choreographed than the opera itself, and people love seeing that. They love having the magic of opera revealed.” (PHOTO: San Francisco Opera Digital Content Manager Ted Schaller.)

For an Open Curtain during Andrea Chénier in September, Ted Schaller, the company’s digital content manager, fielded tweets from the audience on his phone and relayed questions to Daniel Knapp, the company’s director of production. “It was a particularly interesting set change because the stagehands were pulling chandeliers off the ceiling, tearing down walls, putting up new doors, setting up new tables,” Schaller says. “The stagecraft that goes on behind the scenes is almost more choreographed than the opera itself, and people love seeing that. They love having the magic of opera revealed.” (PHOTO: San Francisco Opera Digital Content Manager Ted Schaller.)

SFO management reached an agreement with the stage employees union to accommodate Open Curtain, which started in the summer season of 2015. In September, it began being posted on Facebook Live, and the Andrea Chénier session had more than 3,400 views. Other intermission participants have included composer Bright Sheng and Director Stan Lai to answer questions about the premiere of Sheng’s Dream of the Red Chamber.

SFO management reached an agreement with the stage employees union to accommodate Open Curtain, which started in the summer season of 2015. In September, it began being posted on Facebook Live, and the Andrea Chénier session had more than 3,400 views. Other intermission participants have included composer Bright Sheng and Director Stan Lai to answer questions about the premiere of Sheng’s Dream of the Red Chamber.

Twitter solves the logistical problem of conducting a Q&A in the 3,200-seat War Memorial Opera House. “It’s an easy way to collect questions so we can answer them that night live,” Schaller says. “We have about 10 minutes to take the tweets and get anywhere from two to 15 questions. We aim for about two Open Curtains per run of each show.” He adds that Open Curtain makes the opera experience more interactive, as well as educational and more fun. (PHOTO: Question from the audience for SFO Open Curtain session.)

Death and the Powers in Dallas—and Around the World

Speaking of interactive, Tod Machover’s 2014 Death and the Powers for the Dallas Opera is still gaining kudos for having broken new ground in the performing arts. “I wanted to bring a piece to Dallas that was much more innovative than anything we had done in our history,” says Keith Cerny, who arrived as CEO in 2010. “I wanted people here to think about opera in very different terms.” (PHOTO below right: …Powers composer Todd Machover.)

Speaking of interactive, Tod Machover’s 2014 Death and the Powers for the Dallas Opera is still gaining kudos for having broken new ground in the performing arts. “I wanted to bring a piece to Dallas that was much more innovative than anything we had done in our history,” says Keith Cerny, who arrived as CEO in 2010. “I wanted people here to think about opera in very different terms.” (PHOTO below right: …Powers composer Todd Machover.)

Mission accomplished. Death and the Powers, a tech-heavy work by Musical America 2016 Composer of the Year Machover and his Opera of the Future group at the MIT Media Lab, is to date the boldest use of mobile technology by a major company. The 2014 Dallas performance was simulcast to nine sites in the U.S. and Europe, where audience members could not only watch the opera on a large screen but also use a “Powers Live” app to access it on their tablets and phones. They could even affect certain aspects of what was happening onstage at the Winspear Opera House. (PHOTO: “Powers Live” app initializes for Tod Machover’s opera Death and the Powers.)

Mission accomplished. Death and the Powers, a tech-heavy work by Musical America 2016 Composer of the Year Machover and his Opera of the Future group at the MIT Media Lab, is to date the boldest use of mobile technology by a major company. The 2014 Dallas performance was simulcast to nine sites in the U.S. and Europe, where audience members could not only watch the opera on a large screen but also use a “Powers Live” app to access it on their tablets and phones. They could even affect certain aspects of what was happening onstage at the Winspear Opera House. (PHOTO: “Powers Live” app initializes for Tod Machover’s opera Death and the Powers.)

“This was astonishingly complex from a technical point of view,” Cerny says. “Not only in terms of the actual production, but we had to have bandwidth on three separate satellites to reach all nine locations, and in some locations, an enhanced Wi-Fi network to ensure the app would run without latency. This pushed every technical limit I can think of.” About 1,000 audience members in the remote locations (out of total attendance of 1,700 for the simulcast) downloaded the app. Total cost of the simulcast was about $250,000, largely underwritten by a pair of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. (PHOTO: Dallas Opera CEO Keith Cerny: “I wanted people here to think about opera in very different terms.”)

“This was astonishingly complex from a technical point of view,” Cerny says. “Not only in terms of the actual production, but we had to have bandwidth on three separate satellites to reach all nine locations, and in some locations, an enhanced Wi-Fi network to ensure the app would run without latency. This pushed every technical limit I can think of.” About 1,000 audience members in the remote locations (out of total attendance of 1,700 for the simulcast) downloaded the app. Total cost of the simulcast was about $250,000, largely underwritten by a pair of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. (PHOTO: Dallas Opera CEO Keith Cerny: “I wanted people here to think about opera in very different terms.”)

Death and the Powers, previously staged without a simulcast and app in Monte Carlo, Boston, and Chicago, is an opera about mortality. Its protagonist, a tycoon named Simon Powers, seeks to transcend death by downloading aspects of himself into “The System,” a sort of computer matrix depicted in a sci-fi staging that included a Greek chorus of robots and three 15-foot electronic panels that pulsated with color.

Audience as stage director

Machover, who has long worked at the intersection of technology and art, tapped into the motorized chandelier in the opera house as a vehicle for app users to interact with. “During a couple of scenes, we allowed people on their devices around the world to influence the lighting of the chandelier—how bright and how variable and how synchronized it was—and a little bit of its motion, right over the heads of the audience,” he says. “It gave extra life to the [opera] because people knew they were influencing it, and it made their presence felt in the opera house.”

Machover, who has long worked at the intersection of technology and art, tapped into the motorized chandelier in the opera house as a vehicle for app users to interact with. “During a couple of scenes, we allowed people on their devices around the world to influence the lighting of the chandelier—how bright and how variable and how synchronized it was—and a little bit of its motion, right over the heads of the audience,” he says. “It gave extra life to the [opera] because people knew they were influencing it, and it made their presence felt in the opera house.”

The singer playing Powers (Robert Orth in Dallas) was onstage in only the first and last of the opera’s eight scenes. Otherwise he was inside The System, performing from a booth in the orchestra pit, and the app allowed users to see video of him there. “So people with the mobile devices were seeing something nobody in the opera house could see,” Machover says.

The app also supplied abstract imagery. “There was always something on your mobile screen, even if it was just a texture or a color related to something in the lighting or the movement,” he says. “It never went blank, and like prayer beads, there was always something that happened if you touched the screen—say, if there was a texture on the screen and you moved your finger gently, the texture might follow your finger. All these sorts of things allowed you to feel connected to the mobile device” and, by turns, to the opera. (PHOTO: Audience members used their mobile devices to influence the lighting of the chandelier during …Powers.)

Machover has moved on to incorporate mobile devices into the making of a series of City Symphonies that include homages to Detroit, Toronto, Amsterdam, and Lucerne. “We are currently developing a whole new generation of mobile experiences for our next round of City Symphonies,” he says. “These new apps will let people mix and morph sounds directly on their mobile devices, modify sound mixes depending on the way one moves through the city, and to add these sounds to the overall mix during live performances.”

Car Opera in Los Angeles

As artistic director of L.A.-based production company The Industry, Yuval Sharon says his aim is “to bring new, experimental opera into the civic life of L.A.” Cars are a big part of that civic life, as are mobile devices, and the combination of the two played a central role in Hopscotch, the six-year-old company’s sprawling, site-specific work inspired by the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. It ran last fall, involving 24 limousines driving around Los Angeles and video taken by audience members on smartphones. (PHOTO: The opera Hopscotch involved 24 limousines driving around Los Angeles; video was taken by audience members on their smartphones.)

As artistic director of L.A.-based production company The Industry, Yuval Sharon says his aim is “to bring new, experimental opera into the civic life of L.A.” Cars are a big part of that civic life, as are mobile devices, and the combination of the two played a central role in Hopscotch, the six-year-old company’s sprawling, site-specific work inspired by the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. It ran last fall, involving 24 limousines driving around Los Angeles and video taken by audience members on smartphones. (PHOTO: The opera Hopscotch involved 24 limousines driving around Los Angeles; video was taken by audience members on their smartphones.)

Hopscotch, conceived and directed by Sharon, had a cast of 126 musicians, dancers, and actors, as well as a production team of almost 100. Six composers contributed to the score. With a budget of about $1 million, the 90-minute work was performed three times daily on weekends in a sold-out run (tickets were $125 and $155) in October and November 2015.

Each limousine was occupied by four audience members plus actors or musicians, and on their routes they stopped at sites like City Hall, the Bradbury Building (a location for the 1982 cult film Blade Runner), and the Los Angeles River. At each stop a scene took place that represented one chapter in the overall story. Cameras in the cars produced a live stream shown on 24 monitors that were part of the production’s Central Hub, a temporary structure in a parking lot that was open for free viewing and listening via wireless headphones. (PHOTOS: The Central Hub for Hopscotch was used for both performers… and audience; it was equipped with 24 monitors and wireless headphones.)

Each limousine was occupied by four audience members plus actors or musicians, and on their routes they stopped at sites like City Hall, the Bradbury Building (a location for the 1982 cult film Blade Runner), and the Los Angeles River. At each stop a scene took place that represented one chapter in the overall story. Cameras in the cars produced a live stream shown on 24 monitors that were part of the production’s Central Hub, a temporary structure in a parking lot that was open for free viewing and listening via wireless headphones. (PHOTOS: The Central Hub for Hopscotch was used for both performers… and audience; it was equipped with 24 monitors and wireless headphones.)

Audience as camera-persons “What happened is that in some cars there would be a phone with a camera that we put on a holder, and one of the audience members became the cameraman,” Sharon says. “People were amazingly fluent with it. We are so used to video on our phones capturing friends doing this, that, or the other activity that it felt very familiar. The kind of sharing that we do in our everyday lives actually became part of the opera.” (PHOTO: Yuval Sharon, artistic director of LA-based production company The Industry.)

“What happened is that in some cars there would be a phone with a camera that we put on a holder, and one of the audience members became the cameraman,” Sharon says. “People were amazingly fluent with it. We are so used to video on our phones capturing friends doing this, that, or the other activity that it felt very familiar. The kind of sharing that we do in our everyday lives actually became part of the opera.” (PHOTO: Yuval Sharon, artistic director of LA-based production company The Industry.)

A few critics described Hopscotch as Wagnerian in its ambition to achieve the German concept Gesamtkunstwerk—or “total work of art”—and Sharon suggests, laughingly, that if Wagner was working today he would indeed not just be composing the music and writing the libretto but also designing the app for his operas. “I really have tried to make interactivity an integral part of Industry projects, making sure that the technology doesn’t just feel like it was pasted onto the presentation,” he says. “I think that when the technology becomes a crucial component of the storytelling we’ll really be creating something of our time.”

Mobile and live performance—stimulation or distraction?

Sharon doesn’t think it is necessarily a problem for an audience to have its attention divided between live performance and the screens of mobile devices. “Your attention in a normal opera house is already very divided. You’re looking at the stage, you’re listening to the music, you’re reading the titles. It’s what Brecht called a complex way of seeing in the theater. Your attention is going back and forth between a lot of different stimuli. I think that’s very positive. What people call distraction could actually be stimulation.” However, he acknowledges the challenges. “The problem comes when one person’s divided attention is a distraction to the person sitting next to them. Everybody should still be able to have the experience that they want, and that might be simply sitting and listening to the music. That is going to make it harder for traditional opera companies and symphony orchestras to find their connections to these kinds of technologies.”

John Fleming writes for Classical Voice North America, Opera News, and other publications. For 22 years, he covered the Florida music scene as performing arts critic of the Tampa Bay Times.

John Fleming writes for Classical Voice North America, Opera News, and other publications. For 22 years, he covered the Florida music scene as performing arts critic of the Tampa Bay Times.

Copyright © 2025, Musical America