Digital vs. Print: Three Music Librarians Weigh the Pros and Cons

By John Fleming

November 3, 2015

![]()

While it’s no longer a novelty to see soloists and chamber musicians playing off a digital reader like an iPad, [see Three Committed Converts] symphony, opera, and ballet orchestras are still largely wedded to paper. Will that ever change? And if so, how? When?

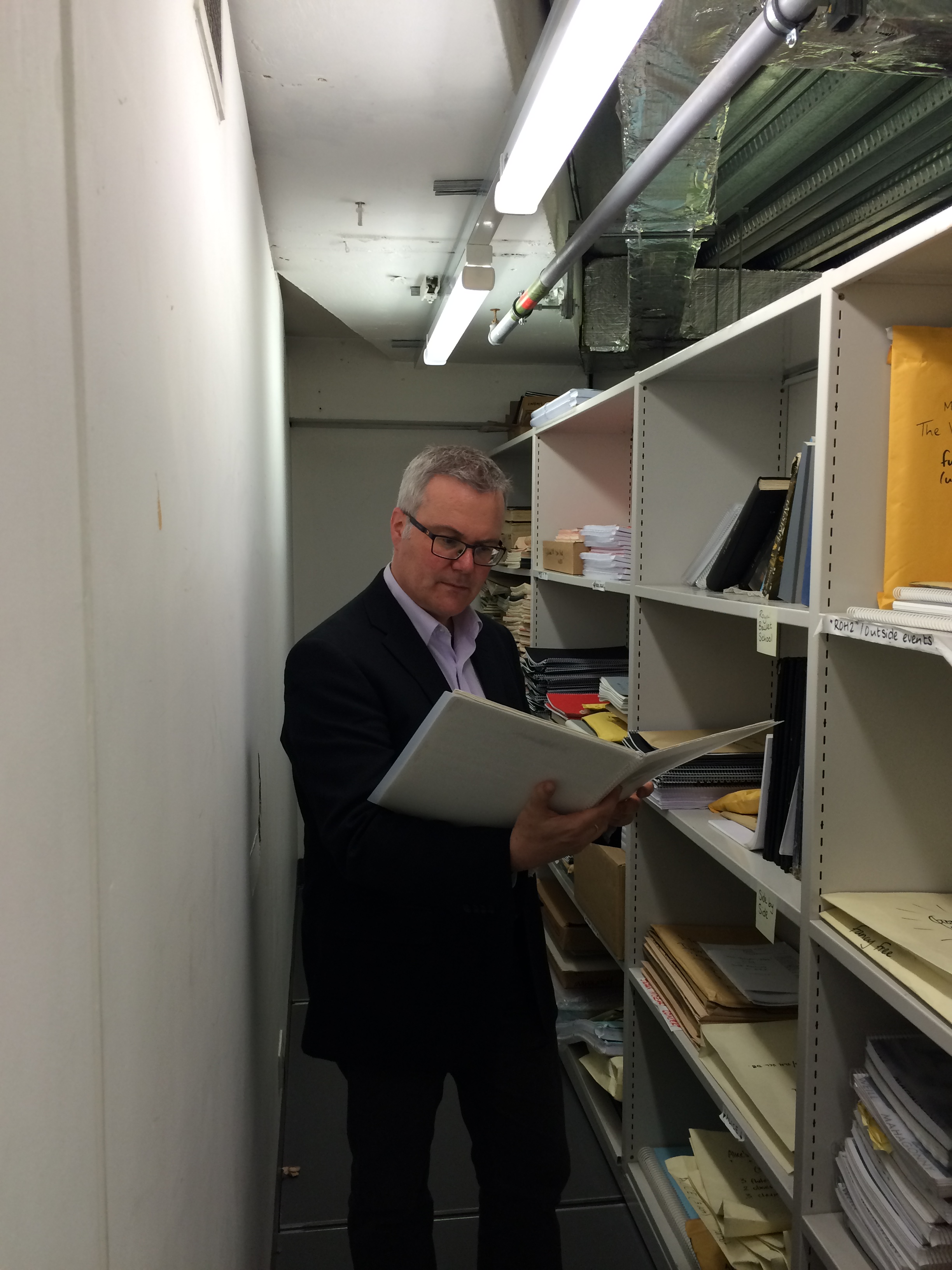

These are questions pondered by many a music librarian, who deal with huge stacks of printed scores and instrumental parts, not to mention the constant shipment of rented sheet music back and forth to publishers. Here’s how librarians at three organizations are balancing digital vs. print.

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center

Chamber musicians are among the early adopters of digital readers, especially Wu Han, co-artistic director of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. “I’m a gadget freak,” says Wu, who uses an iPad to read scores and store her music library. The devices areespecially attractive to pianists because they can solve the page-turning problem with a foot panel. [See below: Page turners are nice people, but….]

Chamber musicians are among the early adopters of digital readers, especially Wu Han, co-artistic director of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. “I’m a gadget freak,” says Wu, who uses an iPad to read scores and store her music library. The devices areespecially attractive to pianists because they can solve the page-turning problem with a foot panel. [See below: Page turners are nice people, but….]

“The digital score, for me, is the way to go,” Wu says. “Our physical library is filled with shelves of paper music, and it is very time-intensive to keep it in good order. The artists come in and out, they pull music, parts go missing, and then we have to reorder it, rebind it, and re-categorize it. Or if we decide not to let the parts out, then if an artist wants a part, we have to copy it. And that’s also cumbersome and time consuming. When you make it all digital, it’s just so much easier to control.” ( PHOTO: Wu Han plays from her iPad while Gilbert Kalish prefers the traditional printed page in a performance of Bartok’s Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion. Credit: Hiroyuki Ito)

Enter Robert Whipple, librarian and operations manager, who is just a few years out of the Sunderman Conservatory at Gettysburg College and now in his fourth season with the Society. He has been charged with helping to bring the 46-year-old organization into the digital age. “It is a priority,” Wu says.

Enter Robert Whipple, librarian and operations manager, who is just a few years out of the Sunderman Conservatory at Gettysburg College and now in his fourth season with the Society. He has been charged with helping to bring the 46-year-old organization into the digital age. “It is a priority,” Wu says.

Whipple spends quite a lot of time scanning scores and parts into PDFs that are uploaded onto servers and organized with ArtsVision, a software program used by the CMS to manage data. “Usually, before the season starts, I scan most of the music that’s going to be performed,” he says. “That way, if people need music, I don’t have to make a copy, I already have it uploaded so I can just print it out or send them a PDF.”

The Chamber Music Society is still a long way from having anything like a complete digital library, but

Whipple is making progress. “Previously, we didn’t scan everything, but I have been pushing for it because it’s ultimately easier,” he says. “If I have everything scanned, I don’t have to copy things year

after year. Once something is scanned, it’s in the system forever. So I’ve just been doing that each season—everything we play, if not all the parts, at least the scores.”

“Page turners are very nice people, but…”

The problem of page turns has drawn many pianists to digital technology. In chamber music, pianists typically play from full scores that, since they can’t be turning pages all the time, require them to have page turners next to them. “Page turners are very nice people, but if you don’t get a good one, it’s hell onstage,” says pianist Wu Han, co-artistic director of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. “The digital reader not only gets rid of that, but it’s great for radio broadcasts and recordings. There’s no paper noise.”

She reports that about half the pianists on the Chamber Music Society roster use digital readers, such as Gloria Chien, Inon Barnatan, and Juho Pohjonen, but among string players, only about 10 percent do. One who does not is her co-director and husband, cellist David Finckel. Says Wu with a shrug: “He just doesn’t like it.”

More players are using digital readers for practice. “I’d say it’s about half and half between musicians asking for PDFs versus hard copies,” Whipple says. “A lot of people who may not be reading off of [a tablet] in concerts still request scores or parts digitally so they can look at the music another way, or just for quick access to a score if they have a question.”

The CMS has an extensive touring program, and it’s not unusual for Whipple to get a call from a musician in the field who needs a part in a hurry. “Once I’ve scanned something in, they can print it out wherever they are. It’s great for emergency situations.”

Unlike the symphony orchestra and opera librarians canvassed for this article, Whipple is not so concerned with including annotations on scores, such as bowings. For the most part, chamber musicians do their own. “I like scans to be as clean as possible so that anyone in the future could make their own notes,” he says. “I erase excessive markings before getting music to the players,

though it can be valuable to have some minimal marking in the part if it’s a lesser-played piece.”

For all of Whipple’s digital orientation, the Chamber Music Society and its librarian still have an old-school backup: “Anytime we do a performance we always have paper copies backstage.”

Royal Opera House

“We’re still surprisingly untouched by technology,” says Tony Rickard, who has been manager of the library of the orchestra of the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden since 2007. “My colleagues in the library… spend most of the day working with pencil and eraser on paper.”

“We’re still surprisingly untouched by technology,” says Tony Rickard, who has been manager of the library of the orchestra of the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden since 2007. “My colleagues in the library… spend most of the day working with pencil and eraser on paper.”

No one plays from a digital reader in performance—uniformity is the rule in the orchestra, and besides, the screens of most tablets are too small to accommodate the traditional two string players per part. Rickard has had demonstrations by manufacturers of paper-free electronic music stand systems, such as eStand in the United States and Scora in Europe. With music on all stands linked, a conductor (or librarian or even publisher, theoretically) can send annotations from a central device to everyone’s parts. Some see this as the future for orchestras. Rickard is not so sure.

“The main problem that it seems to solve is the one of page turns, particularly with long orchestra pieces, and you can imagine opera parts that go on forever. But it doesn’t really seem to solve much else that couldn’t be solved in other ways, taking into account the cost and inconvenience of switching to a new system.”

“The main problem that it seems to solve is the one of page turns, particularly with long orchestra pieces, and you can imagine opera parts that go on forever. But it doesn’t really seem to solve much else that couldn’t be solved in other ways, taking into account the cost and inconvenience of switching to a new system.”

Rickard figures that the Royal Opera would need a digital system for up to 100 players in the orchestra. “At a rough estimate,” he says, “you’re probably looking at 60,000 euros [about $67,000] or more to replace a paper system that works fine. And what about the built-in obsolescence of most technology? Would we need to buy a new system every few years? This is probably me just being old-fashioned, but I don’t see it happening.”(PHOTO: eStand score reader)

Then there’s the issue of reliability. To work properly, the Scora system needs strong, uninterrupted wifi—not always a sure thing. “What you really couldn’t have is a performance conking out because of some technical glitch. It happens occasionally onstage…but there you can sort of see when it isn’t working, and the audience has a tolerance for it. But if the music stands go down, I don’t think that would go over very well.”

With its history reaching back to Handel’s appointment as musical director, in 1719, the Royal Opera has a vast stock of music on paper, which includes not just opera but also ballet, stored throughout its building and offsite. Where digital technology often comes into play now for its librarians is when they use software like Photoshop or Sibelius for notation to prepare new sets of standard repertory. “Fixing page turns, bar numbers, bowings, errata, that sort of thing,” Rickard says, citing recent projects to clean up La Traviata and Eugene Onegin scores.

They also move into the digital realm with commissions, especially with the the inevitable last-minute changes. When Thomas Adès’s The Tempest was set to premiere at the Royal Opera, the libretto was rewritten very late in the process. Instead of working from a printed score, as is customary, the company received a stream of revisions digitally from the publisher. “Adès made quite a lot of edits after having heard rehearsals, and then it was my job to implement them,” recalls Rickard. “In the old days, we would have had couriers running around London all day, every day, but I was able to make the changes from PDFs. A similar situation happened with Mark-Anthony Turnage’s Anna Nicole in 2011.”

They also move into the digital realm with commissions, especially with the the inevitable last-minute changes. When Thomas Adès’s The Tempest was set to premiere at the Royal Opera, the libretto was rewritten very late in the process. Instead of working from a printed score, as is customary, the company received a stream of revisions digitally from the publisher. “Adès made quite a lot of edits after having heard rehearsals, and then it was my job to implement them,” recalls Rickard. “In the old days, we would have had couriers running around London all day, every day, but I was able to make the changes from PDFs. A similar situation happened with Mark-Anthony Turnage’s Anna Nicole in 2011.”

Los Angeles Philharmonic

To supplement its own library of scores, a symphony orchestra rents a greater volume of music than any classical organization, and especially the Los Angeles Philharmonic, with its summer Hollywood Bowl concerts. “We rent up to 70 pieces of music a year in addition to our standard, non-copyrighted works [that the orchestra owns] and the works we have commissioned,” librarian Kazue McGregor says. For the most part, the orchestra still gets its rental music on paper, but pops programs often entail digital parts.

To supplement its own library of scores, a symphony orchestra rents a greater volume of music than any classical organization, and especially the Los Angeles Philharmonic, with its summer Hollywood Bowl concerts. “We rent up to 70 pieces of music a year in addition to our standard, non-copyrighted works [that the orchestra owns] and the works we have commissioned,” librarian Kazue McGregor says. For the most part, the orchestra still gets its rental music on paper, but pops programs often entail digital parts.

“In the summer we do a lot of original arrangements for Hollywood Bowl concerts,” says McGregor, who has worked in the library since 1984. “Rock groups like Bright Eyes or Death Cab for Cutie often haven’t performed with an orchestra before, so they’ll have some orchestral arrangements done, and they’ll arrive to the library on PDFs.” Those have to be downloaded and printed out. When there a lot of them, as in last year’s four movie nights with all original arrangements, things can get complicated—not to mention a little crazy.

When Harry Connick Jr. played the Bowl, his band members played off digital readers. McGregor was intrigued by their system. “They had 40 to 60 pieces on their readers, and all the librarian had to do was put the music in order on the [digital] system.”

“That certainly would solve the problem of playing outdoors and having your music fly off the stand,” she continues. “We use old-fashioned clothes pins.”

Everything the LA Phil performs is on paper, but last season, the orchestra purchased iPads for percussionists to use in Michael Gordon’s Timber, an hour-long piece for six percussionists on the Green Umbrella contemporary music series. With sticks in their hands and no break in the music, the players couldn’t turn pages quickly enough. “We try to accommodate, even with paper copies, complex page turns by using multiple music stands and so forth,” McGregor explains. “But this involved unending, complex page-turning.” Enter the iPad.

Old World vs. the New World

McGregor thinks it will take a turnover in players before symphony orchestras really go digital. “When you have a whole generation of musicians who went through music school playing on tablets, the transition will be easier. Right now, we have too many people with a mental and emotional connection to the sheet music. They don’t want the generic look of digitized music. They want the older feel, and I respect that.”

Is podium resistance also an issue? “Absolutely,” says McGregor. “I run into conductors who don’t even want to use a newly revised version of a score because they grew up learning the old one. Even though it’s ugly and has corrections written in all sorts of colored pencil, that’s the one they want. So I doubt they’re going to want to switch to a tablet.”

John Fleming writes for Classical Voice North America, Opera News, and other publications. For 22 years, he covered the Florida music scene as performing arts critic of the Tampa Bay Times.

John Fleming writes for Classical Voice North America, Opera News, and other publications. For 22 years, he covered the Florida music scene as performing arts critic of the Tampa Bay Times.

Copyright © 2025, Musical America