Special Reports

Competition Insights from the Horse’s Mouth

An interview with Benjamin Woodroffe, secretary general of the World Federation

As secretary general of the Geneva-based World Federation of International Music Competitions (WFIMC), Benjamin Woodroffe coordinates the operations of 125 music competitions in 40 countries. In 2017 alone, WFIMC’s members held about 60 competitions averaging 225 applicants each, many of them fresh out of conservatory.

As secretary general of the Geneva-based World Federation of International Music Competitions (WFIMC), Benjamin Woodroffe coordinates the operations of 125 music competitions in 40 countries. In 2017 alone, WFIMC’s members held about 60 competitions averaging 225 applicants each, many of them fresh out of conservatory.

A native of Australia, Woodroffe, 47, studied architecture, French literature, and art history at the University of Adelaide. Before coming to the Federation, he served as general manager of the Melbourne International Chamber Music Competition from 2005 to 2015.

WFIMC celebrated its 60th anniversary in December, also the month that Musical America caught up with Woodroffe to discuss the changing landscape of international music competitions.

Musical America: What are the top three competition disciplines among WFIMC members?

Benjamin Woodroffe: Looking at the membership today, 33 percent are piano competitions, 11 percent are violin competitions, and 23 percent are multidiscipline, meaning, for instance, Germany’s ARD Competition and Belgium’s Queen Elisabeth, which change disciplines either each year or have several at the same time.

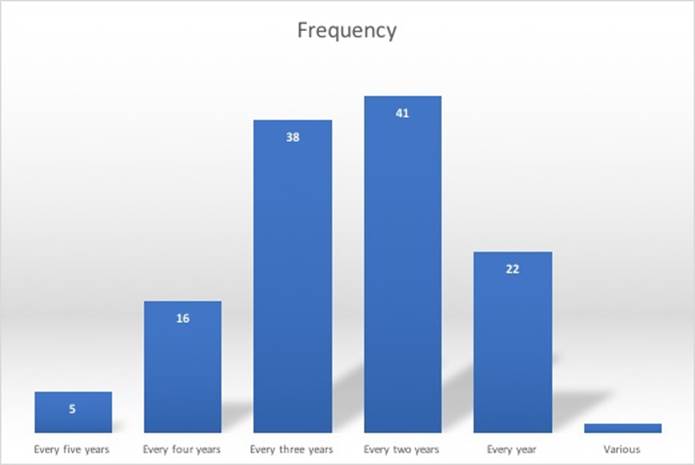

(PHOTO: Frequency of competitions among WFIMC members. Source: World Federation of International Music Competitions.)

MA: Are there trends in competition disciplines?

BW: In the last five years, there has been a trend toward conducting competitions. And that’s coming from orchestras themselves. Trondheim in Norway is the most recent, and we also have them in Armenia, France, and Italy. We don’t have one yet in North America, but watch this space.

MA: Geographically, are there growth areas for competitions?

BW: We’ve seen it recently in China. The city of Harbin, for instance, has made a major push to become a center for music. They’ve built incredible concert and opera houses, and established competitions such as the Schoenfeld International String Competition.

MA: Are you at a competition every week?

MA: Are you at a competition every week?

BW: I can’t get to every one; in 2017 there were almost 60 and the bulk were in May and September. Many of our competitions are connected with academic institutions, so venue access and support often drive the timetable. The other factor that drives competition scheduling is orchestra availability. [All members’ final rounds must be with orchestra.] (PHOTO: The Harbin Grand Theater, site of the Schoenfeld International String Competition.)

MA: What are competitions looking for in musicians these days?

BW: More than virtuosic talent, competitions reflect what is required of a performing musician today. They are looking for artists—true, rounded, whole musicians.

MA: Why join the WFIMC?

BW: First of all, it’s a stamp of artistic and operational credibility [see membership guidelines]. You’re joining a like-minded group of competitions. You have to prove that you’re sustainable and on-going, and that you have a clear focus and operate fairly. And you join because we represent you and advocate on your behalf. We work with festivals, we work with agents, we have a large network available to members.

I often say the Federation has 125 different children. Each competition has a very different niche, a different sense of purpose, a different sense of place, a different business model, and they are different ages. There is no cookie-cutter model.

MA: What’s the biggest cash prize in international music competitions?

BW: The Honens Piano Competition has the top prize, of $100,000 Canadian, plus three years of engagements. The Cliburn is close behind, with $50,000 for the gold medalist and a similar commitment to engagements for three years.

But competitions are about so much more than the cash prize. These days, they’re all-encompassing, with outreach events that send candidates into schools. The ultimate value for the laureates is the engagements and the mentoring and the introductions that come from participating.

MA: Performance opportunities for young musicians are hard to come by, with or without competition wins.

BW: That’s one reason why competitions are organizing more engagements, actively working with festivals and venues and concert programmers to secure laureate opportunities in advance, so that when the final rounds are over, there’s a guaranteed calendar for the winners. Our members are brokering more of these appearances themselves, rather than agents, although some have agreements with particular agents.

MA: What about mentoring and management?

BW: Obviously, the larger competitions can afford a greater degree of that. For example, the International Franz Liszt Competition in Utrecht [Netherlands] offers laureates a three-year coordinated

professional mentorship program, which covers everything from agent representation to media training to stagecraft to website production to contractual business training.

MA: In choosing laureates, does the Federation have specific voting rules?

BW: Every competition has its own rules and its own voting system. For us, the crucial requirement is that the system is understood by everyone—jury, candidates, audience.

MA: What are your feelings about teachers as jurors and judging their own students or students of colleagues?

BW: Okay, I’m going to be really honest. If there’s one topic we spend the most time on, it would be this.

Certain members say they will never have a teacher on the jury; others say there are some very good teachers who know how to behave and it would be a pity to say no them automatically. The federation recommends that teachers not be allowed to vote for their students, and we ask all jurors to declare their interest before the event begins. But every member manages its implementation of [these guidelines]. The Federation is not a police organization.

By the way, the trend is shifting more toward a performing-artist jury than teacher juries. Also, remember that every competition is operating in a different place, in a different culture, in a different way of thinking. Some evaluate candidates with scores from, say, 1 to 10; others use a yes or no voting system.

MA: Numerical scoring can seem pretty complicated. Is a yes-no system simpler?

BW: Personally, I prefer it. Do you want this candidate to advance to the next round—yes or no? Federation members use both. But it’s up to every competition. The most important thing is that voting is anonymous, and only the results are then shared with the jury.

MA: How do you prevent certain jurors from overly influencing the process?

BW: It is a clear policy of the federation that discussion between jurors is forbidden.

MA: What about bias in favor of musicians in competitions in their home countries?

BW: They have a huge hometown advantage with the audience, all the cheering and so forth, but I think that in terms of performance they’re under more pressure to play even better than normal, to win for the home team. Sometimes being the local candidate for finalist gets you more interest, and if you’re prepared to say what you need to say musically at the right time in the right place, you can take off.

MA: Do you receive formal complaints about competitions?

BW: Not many. Since I arrived, I’ve received two questions from candidates who have taken part in Federation competitions, and both were about operational matters, not artistic.

MA: How important is the screening jury, the pre-competition jury? It might be more important than the regular jury.

MA: How important is the screening jury, the pre-competition jury? It might be more important than the regular jury.

BW: You’re absolutely right. The trend now is to have a very significant screening jury. Ideally, they are traveling to listen to the candidates in different cities around the world—the same set of ears is hearing candidates in different places.(PHOTO: Winners of the Fifteenth Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, June 10, 2017. Left

to right: silver medalist Kenneth Broberg, of the U.S.; gold medalist Yekwon Sunwoo of South Korea; and bronze medalist Daniel Hsu, of the U.S. after receiving their awards at the Fifteenth Van Cliburn International Piano Competition held at Bass Performance Hall in Fort Worth, Texas. PHOTO: Ralph Lauer.)

MA: How can a competition avoid a cutthroat atmosphere?

BW: It is up to us to build a platform and put the right framework in place so that these candidates are treated with respect in the same way you would treat a concert artist. They’re given adequate rehearsal time. They’re given access to instruments. They’re given host families to stay with. They’re given transportation. They’re treated as an artist, not as Competitor No. 24.

Most of our competitions, even the preliminary rounds, are performed before a very healthy audience, not just a row of austere jurors in the back of a hall, and many performances are streamed.

MA: Streaming competitions seems to have become more prevalent.

BW: It’s a reflection of two things. Competitions are an amazing human-interest story; young artists are throwing themselves into repertoire that we all know. And it’s live, so the unexpected can happen—the brilliant performance that surprises.

MA: Are there leading examples of competitions and streaming?

BW: I’m careful not to favor one competition over the other, but take the 2017 Cliburn. I was there in Fort Worth, and they partnered with Medici. tv and invested heavily in streaming. In 2018, the Leeds Piano Competition is partnering with Medici, and not only streaming the competition but also parts of the auditions. The Rubenstein in Tel Aviv streamed their competition. The Queen Elisabeth has a longstanding streaming partnership, and the competition in Montreal also streams. A lot of our competitions are doing this, but they’re doing it in different ways.

MA: It can be heartbreaking when candidates travel halfway around the world and then are eliminated after the first round. Maybe they’re terrific musicians who had a bad day. Is there any way around that, or is it just a fact of competition life?

BW: There has been a shift in the last 10 years to let candidates perform more than once, for this very reason. The first voting may take place after the first two rounds, to give the artists a chance to settle in, to acclimatize, to iron themselves out. The federation is also pushing for the candidate to have more choice of program and repertoire.

I know in Melbourne, if we were flying a string quartet from Germany to Australia we were not going to let them play just once and then put them on a plane and send them home. They all played two rounds and candidates were invited to stay until the end of the competition so they were able to listen and take their measure against other quartets. Yeah, competitions are about the jury and so forth, but they are also about the personal discovery of finding yourself as a musician.

John Fleming, a regular contributor to Musical America, is president of the Music Critics Association of North America. He writes for Classical Voice North America, Opera, and others. For 22 years, he covered the Florida music scene as performing arts critic with the Tampa Bay Times.

WHO'S BLOGGING

Law and Disorder by GG Arts Law

Career Advice by Legendary Manager Edna Landau

An American in Paris by Frank Cadenhead

FEATURED JOBS

FEATURED JOBS

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO