Untangling the Bundle: Grand Rights vs. Small Rights

By Steven Lankenau

June 3, 2014

In Busted: the Top 10 Myths of Copyright, lawyer Brian Goldstein writes, “Permission to use a copyright is granted (or not) by the owner in the form of a license. Licensing the ‘rights’ to use a piece of music means you have the permission of the owner to do so.”

In Busted: the Top 10 Myths of Copyright, lawyer Brian Goldstein writes, “Permission to use a copyright is granted (or not) by the owner in the form of a license. Licensing the ‘rights’ to use a piece of music means you have the permission of the owner to do so.”

But what kind of rights? Grand rights, small rights, sync rights, rental rights…? Small wonder that, in music-publishing jargon, the different categories of rights are often referred to as one “bundle.” The following two articles should help untangle a few of the knots.

Question: Which of these requires a license for grand rights? Which requires one for small rights?

- A gala evening of arias from different American operas in concert.

- An orchestra opens its season with a semi-staging of Sweeney Todd.

- A play on Broadway includes a couple dancing to an Astor Piazzolla tango.

- A young choreographer creates a solo to Beyoncé’s new CD performed in a tiny downtown loft.

If you had to guess at the right answer, you are not alone. Ascertaining the difference can get complicated, especially since there is no statutory definition of grand rights, just broad definitions understood (or misunderstood) by the industry. Incidentally, the only one of the four scenarios above that is not grand rights is the first. What follows is should help explain why.

Small Rights

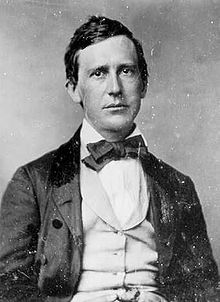

Stephen Foster is generally considered America’s first hit-maker, having penned such classics as Oh! Susanna, Camptown Races, and My Old Kentucky Home. But he died penniless because, in his day, anyone could perform any music without ever acknowledging—much less compensating—the composer.

Stephen Foster is generally considered America’s first hit-maker, having penned such classics as Oh! Susanna, Camptown Races, and My Old Kentucky Home. But he died penniless because, in his day, anyone could perform any music without ever acknowledging—much less compensating—the composer.

Enter Victor Herbert, Irving Berlin, and a number of other prominent songwriters who, in 1913, banded together to form the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) to create a system in the United States for collecting money from live performances. A second major Performing Rights Organization (PRO), Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI), emerged about 20 years later, and today we understand that when a piece of music—from a pop song to a symphony— is performed or broadcast, the person who wrote it should be compensated. Most composers belong to either ASCAP or BMI; it is those PROs that collect fees from music users and distribute royalties to the composers and appropriate publishers.

Enter Victor Herbert, Irving Berlin, and a number of other prominent songwriters who, in 1913, banded together to form the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) to create a system in the United States for collecting money from live performances. A second major Performing Rights Organization (PRO), Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI), emerged about 20 years later, and today we understand that when a piece of music—from a pop song to a symphony— is performed or broadcast, the person who wrote it should be compensated. Most composers belong to either ASCAP or BMI; it is those PROs that collect fees from music users and distribute royalties to the composers and appropriate publishers.

Grand Rights

PROs are only responsible for licensing the performance of nondramatic works, a.k.a. small rights. Authorization for “dramatico-musical” works—operas, musicals, oratorios, revues, ballets, and other works that tell a story—can only be authorized and licensed for use by the copyright holder, which is generally either the creator or the creator’s publisher. These are “grand performing rights,” usually shortened to “grand rights.”

Grand rights works can be put into two general categories:

- Works conceived to tell a story with words and music such as musicals, operas, and oratorios. Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific, Berg’s Wozzeck, and Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex are examples.

- Existing or commissioned works that are used in certain extra-musical contexts, such as with choreography, stage action, or as part of a play.

The fee for grand rights performances is determined by variables such as the size of the piece, the number of performances, and the scope of the presentation; this is all generally a matter of negotiation between the user and the rights holder. In addition to compensation for grand rights use, the licensee must also get approval. You might think that setting Billy Budd on an intergalactic spacecraft is a genius idea, but the Britten estate might not be quite so enthusiastic; it is always best to seek approval sooner rather than later in the process.

Works conceived to tell a story, such as operas,musicals, or oratorios

Musicals, operas, oratorios, and other similar works that are written to tell a story (even if the story is fairly abstract) are treated as grand-rights works when performed in their entirety or when enough of the piece is performed to convey a section of the story, for example an act, a scene, or a significant excerpt. This means that regardless of the nature of the performance—staged, semi-staged, or in concert—the dramatic nature of the work is being put across to the audience. Examples:

Musicals, operas, oratorios, and other similar works that are written to tell a story (even if the story is fairly abstract) are treated as grand-rights works when performed in their entirety or when enough of the piece is performed to convey a section of the story, for example an act, a scene, or a significant excerpt. This means that regardless of the nature of the performance—staged, semi-staged, or in concert—the dramatic nature of the work is being put across to the audience. Examples:

- A concert performance of Sweeney Todd, without costumes, dialogue, or movement

- A performance of a song or a selection of songs from Porgy and Bess, with the singers in costume and in character

- A performance of Amahl and the Night Vistors backed by piano

In contrast, standalone arias and numbers can be treated as small rights, as would instrumental excerpts of operas and musicals. Examples:

- An orchestral performance of Symphonic Dances from West Side Story

- A performance of a song or selection of songs from the opera Dead Man Walking with the singers in concert dress, but with no dialogue or stage action

- That gala evening of American arias mentioned above

Existing or commissioned music that is used in certain extramusical contexts

This is the other side of the dramaticomusical coin. Here, an explicit narrative or story is less important than the fact that a choreographer, director, or other artist is adding another layer to the copyrighted piece of music. It is safe to say that if you are taking a song or concert work of any sort and creating a dramatico-musical work, you should contact the copyright owner to obtain permission to use the music in the proposed context and to determine the appropriate fee for its use. Examples:

- Choreographing Aaron Copland’s Rodeo (though a concert performance of the complete score or the Four Dance Episodes from Rodeo is not a grand rights performance)

- Using recordings of Stravinsky excerpts in a play about George Balanchine (or anyone else, for that matter)

- Creating a one-woman show about the life of Judy Garland and singing Over the Rainbow

Grand Rights Aren’t Always That Grand

A grand rights license is required regardless of how the music was created or is being performed. Even if you stage an opera using piano-vocal scores purchased from sheetmusicplus or dance to music purchased on iTunes, you must acquire a grand rights license (you also have to get permission to use the specific recording from the label or whoever owns the master, but that’s another story altogether).

Steven Lankenau is the senior director of promotion at the New York offices of Boosey & Hawkes, where he oversees composer management and repertoire-promotion strategy throughout North and South America. Previously he worked in programming at the Brooklyn Philharmonic and at Lincoln Center.

Copyright © 2024, Musical America