Special Reports

The Story of O (and P)

As a sleepy associate at a D.C. law firm one morning 21 years ago, I’d been unable to duck an assignment involving “immigration law,”

whatever that was. I soon discovered the topic involved a set of rules so obscure that I needed a real immigration lawyer (a rare species at the time) to help interpret. I found one, and began a dizzying descent into the morass that U.S. immigration law was, even then. Not long after, Cathy French, then-president of what is now the League of American Orchestras, asked the League’s general counsel, Lee R. Marks, a partner of mine, whether the new O and P visa classifications in the Immigration Act of 1990 (IMMACT90, enacted November 29, 1990) really meant what they said. Previously, artists were required to be of “distinguished merit and ability.” Now, they had to be of “extraordinary ability…demonstrated by sustained national or international acclaim.” If the base line standard for qualifying for an O visa was that stringent, French suggested, the U.S. had abruptly raised daunting barriers to all but the most famous artists from entering the U.S., thereby eviscerating the vibrant international cultural exchange it had previously had enjoyed.

The Lonely Goatherd

The Lonely Goatherd

Within a few weeks, I found myself as immigration counsel to a growing coalition of distraught arts-related organizations, from the League to the International Society of Performing Artists, to the Big Apple Circus to assorted artist managers, who understood the danger they faced and the need for a unified stance to lobby Congress to change it. Still, they had never before had to organize so broadly, and they knew precious little about the topic of immigration.

I was no great expert myself. Up till then, the U.S. immigration process had been informal, with problems resolved in phone calls or meetings between the petitioning entity and immigration personnel. Similarly, U.S. consulates were far more approachable than they are now. Guided by French and Marc Scorca, still president and CEO of OPERA America, and ably assisted by Rick Swartz, a professional strategist on public policy issues, including immigration, I went to work untangling the knots and double knots our government had wrought.

A Meeting with the Senator’s Office

I arranged for a meeting with Jerry Tinker (then majority staff director for the Senate Subcommittee on Immigration and Refugee Affairs), acting for Senator Ted Kennedy (the Subcommittee’s chairman, and friend to organized labor and the arts). We also met with Jack Golodner, then president of the AFL-CIO’s Department for Professional Employees. I explained the problem the new law (IMMACT90) posed, and that I’d been unable to find anyone in the House of Representatives, which had originated the provisions in question, willing to take responsibility for them. Asked by Tinker for his reaction to this state of affairs, Golodner responded with a shrug, saying, “I really have no idea how they got there.”

I was skeptical about that response: Immigration and Naturalization Service (legacy INS, now USCIS) had by 1990 begun consulting with organized labor—the Hollywood unions in particular—on whether particular foreign performers were indeed of distinguished merit and ability. I suspected that Congress had passed the new law in response to organized labor’s request. Still, Tinker knew that the unions would have to be part of the solution, lest they prevent one altogether. Tinker then confessed that neither he nor the Senator had been aware of the O and P provisions before the Senate passed the new law, but, he said, he had a simple plan: Golodner and I were to walk out the door and return only when we had a deal acceptable to all concerned, at which point the Senator would make sure the deal became law.

Two Coalitions Too Many

Coalition politics are whatever the opposite of fun is, and I had two coalitions to deal with: the arts-related groups on one side, and organized labor—American Federation of Musicians, International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, etc.—on the other. Organized labor wasn’t really very “organized,” since it too was a coalition, with all the complications that entails. Still, I think Golodner had the easier time of it, as AGMA and IATSE have a lot more in common than, say, Dance/USA and the Big Apple Circus.

Nine months of meetings and negotiations followed, and I spent more time herding my arts-related cats than meeting with Golodner. The former had two very understandable problems: they knew virtually nothing about immigration law and procedure, and they distrusted organized labor. This meant that, while I was bringing the arts-related coalition up to speed on immigration law, I had to negotiate with Golodner simply to come up with concepts and talking points I could use to illustrate the problems and possible solutions to my own coalition members. I suspect Golodner was doing the same on his side.

The Consensus, the Bill, the Law

The Consensus, the Bill, the Law

With the able assistance of Mr. Swartz, a seasoned coalition expert who knew how to bang heads, a lot of back and forth with Golodner, and some interesting meetings with Golodner’s coalition members, we eventually found common ground. Organized labor, as it turns out, understood that it could not be perceived as a stumbling block to international cultural exchange. Rather, it wanted in effect to be able to monitor the influx of foreign artists, and it wanted protection

from cheap labor. Meanwhile, the goal of the arts-related coalition was simply to lower the barriers to vigorous international cultural exchange as much as possible, while ceding as little leverage as possible to organized labor.

True to his word, Senator Kennedy introduced a bill containing the compromise the two coalitions had wrought. The bill did something exceedingly unusual by today’s sorry standards: it attracted the support of a large majority of both political parties. Before it could become law though, the bill itself had to be stitched word by word, line by line, into the existing Immigration and Nationality Act. For that purpose, a marvelous staff attorney and technician on the House side and I spent hours on the phone late at night going line by line through the language, trying to ensure that the technical effects of the bill would be as the two coalitions—and Congress—intended.

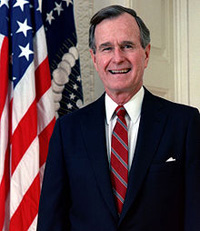

On December 12, 1991, President Bush signed into law the Miscellaneous and Technical Immigration and Naturalization Amendments of 1991, containing the O and P provisions as we now know them. The essential compromise was that the revised law required only that artists have “distinction,” a defined term that effectively reinstated the lower “distinguished merit and ability” standard of the old law. Also, the new standards for performance groups and culturally unique performers and groups were adjusted, primarily to discourage importation of foreign productions not associated with a particular group.

On December 12, 1991, President Bush signed into law the Miscellaneous and Technical Immigration and Naturalization Amendments of 1991, containing the O and P provisions as we now know them. The essential compromise was that the revised law required only that artists have “distinction,” a defined term that effectively reinstated the lower “distinguished merit and ability” standard of the old law. Also, the new standards for performance groups and culturally unique performers and groups were adjusted, primarily to discourage importation of foreign productions not associated with a particular group.

In return, organized labor got a seat at the table, so that it would have a chance to see and opine with respect to most arts-related petitions. Until the Immigration Act of 1990, the U.S. immigration process had been informal, with problems resolved in phone calls or meetings between the petitioning entity and immigration personnel. Little did we anticipate then that, whatever else they may have gained, the arts-related unions also gained the potential for a revenue stream. While none of the unions initially charged for the newly required “advisory opinions,” today it can cost as much as $500 simply to obtain a letter stating that the union does not object to the petition!

The next step, too, went relatively smoothly, in that the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (legacy INS, now USCIS) reached out to the coalition members, solicited their views, then produced a workable set of interim regulations on April 9, 1992, just after the current O and P provisions took effect. I range from sentimental to maudlin as I recall that all this happened without anti-immigrant sentiment or the intervention of PACs, super PACs, 501(c)(4)s, or Las Vegas billionaires.

Off the Page and Into the Fray

I filed my first O and P petitions on behalf of foreign artists soon after. One of the earliest petitions I remember involved a small New York City agency that had booked a tour of an Italian opera company. It had filed the initial petition on its own, and legacy INS had responded by asking for “an advisory opinion from a peer group (or other person or persons of [petitioner’s] choosing, which may include a labor organization) with expertise in the specific field involved.” Yes, this is the statutory language and, yes, its imprecision reveals the political compromise between the unions and the arts organizations that lies beneath.

The agency/petitioner responded entirely logically: the agency’s head got the head of another agency in the adjacent office to write a letter singing the praises of the opera company in question. Why not? After all, the statute seemed to say that the advisory opinion could come from a union, so that meant it did not have to come from a union, right? “Wrong,” said legacy INS. The tour was to begin the following week; I got the call on a Tuesday evening.

It happens that I had been planning to go to New York City the next day anyway, so I told the frantic client I would be at his office first thing in the morning. We spent several hours redoing the petition, we obtained an advisory opinion from AGMA that afternoon, I took the papers the next day to my own local legacyINS office, and filed them using an emergency procedure no longer available. Friday morning, after I spent some time on the phone with an officer from the Vermont Service Center, Vermont cabled its approval to the U.S. Embassy in Rome. By then, my client had contacted the Vatican, which had contacted the Embassy, which, in turn, sent a consular officer to the company’s dress rehearsal, where he issued the visas. The company members flew to the U.S. that Sunday, rehearsed Monday and began performing Tuesday. Now that was close.

It happens that I had been planning to go to New York City the next day anyway, so I told the frantic client I would be at his office first thing in the morning. We spent several hours redoing the petition, we obtained an advisory opinion from AGMA that afternoon, I took the papers the next day to my own local legacyINS office, and filed them using an emergency procedure no longer available. Friday morning, after I spent some time on the phone with an officer from the Vermont Service Center, Vermont cabled its approval to the U.S. Embassy in Rome. By then, my client had contacted the Vatican, which had contacted the Embassy, which, in turn, sent a consular officer to the company’s dress rehearsal, where he issued the visas. The company members flew to the U.S. that Sunday, rehearsed Monday and began performing Tuesday. Now that was close.

In Orbit

I have since concentrated on arts- and entertainment-related U.S. immigration matters—petitions to USCIS, visa applications to U.S. Consular Sections or Consulates abroad, entry-related problems with what is now U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and permanent residence issues. The compromises reached by the coalitions back then remain largely intact, but the environment has deteriorated, at times badly, such that the process of bringing foreign artists and entertainers into the U.S. is more complicated and costly than it should be.

If you need to bring an artist in from abroad, my best advice to you is to visit Artists from Abroad and plan as far ahead as possible. This way, if and when you encounter the inconsistencies and occasional outrages perpetrated by USCIS and, once in a while, the Department of State, you might at least have some time to deal with the problem.

Jonathan Ginsburg, of Fettmann Ginsburg PC, in Fairfax,VA, a full-time immigration lawyer, specializes in arts- and entertainment-related immigration, including temporary work-related O and P visas, permanent residence, and related consular matters. Author of the immigrationrelated portion of Artists from Abroad, he may be reached at jginsburg@fettmannginsburg.com.

WHO'S BLOGGING

Law and Disorder by GG Arts Law

Career Advice by Legendary Manager Edna Landau

An American in Paris by Frank Cadenhead

FEATURED JOBS

FEATURED JOBS

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO